Belonging to the Maldhari community of Gujarat, a pastoralist society, Jaisingh has trudged his way to Delhi with his fellow pastoralists to attend Living Lightly, an exhibition which aims to capture the pastoral way of life. Co-organised by Sahjeevan, and the Foundation for Ecological Security, the exhibition underway at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), depicts the art and culture of the pastoralists through various shows. Panel discussions, dastangoi, live music, film screenings, art, poetry, photography, live performances, games, conversations, walking trails and handcrafted artifacts all showcasing pastoral culture are part of the overall event.

Curator Sushma Iyengar, who actively engages with social issues concerning crafts management and community rehabilitation, has been working on this exhibition for the past three years. She intends to showcase the inextricable link between humans, land and ecology. “I have been living and working with the pastoral community for many years. Pastoralism contributes hugely to our economy and culture, yet it is very invisible. Society at large gives more significance to settled communities rather than people on the move. Pastoralists are thus neglected and I think it is important for society at large to appreciate the role and life of such communities. This exhibition is an attempt to start a conversation among pastoralists and society.”

Having lived in Kutch, Gujarat for 28 years now, Iyengar has worked with different craft and music communities, and has observed different aspects of the people’s life — such as economy, science, culture, craft, art and their spiritual practices. “With the contribution of other curators and my own experience, we have put together this show. There are artists and craftsmen from the pastoral community and there are others who are not part of the community, but have lived together and have contributed their expressions to the pastoralists’ life. There aren’t too many organisations working with pastoralists’ issues and we need more people to work in this regard. With the workshops and conferences as part of the show we aim to influence certain policies for the welfare of pastoralists and society alike.”

“With the contribution of other curators and my own experience, we have put together this show. There are artists and craftsmen from the pastoral community and there are others who are not part of the community, but have lived together and have contributed their expressions to the pastoralists’ life.”

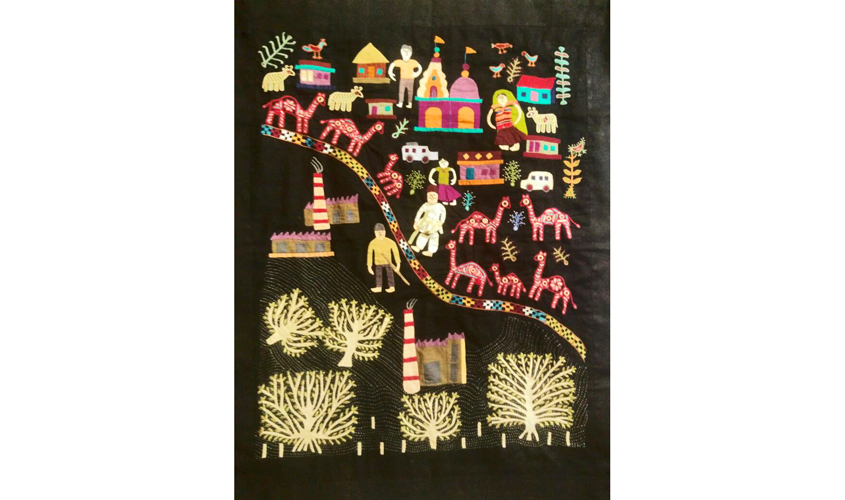

Meguben, a woman in her 50s from the Rabari community in Gujarat, has been making colourful embroidery since childhood. Her subject matter comes from the happenings or stories of her village. It is not surprising then that one of her embroidery pieces is a factory design along with other motifs. She can’t recall the time when the factory popped up in her village. “It has been many years now since factory was built here. Due to the presence of factories, various difficulties for pastoralists have emerged. There has been considerable loss of grazing grounds. The future seems bleak,” says Meguben.

Similar issues are encountered in the Telangana state where pastorals herd Deccani sheep. The weaving of woollen blanket gongadi is their major handicraft. The woven blankets are on display and sale at the venue. In conversation with the pastoralists of erstwhile Medak district in Telangana, assisted by Charanaya, a social worker and a member of the Food Sovereignty Alliance (an organisation aiming to guide the way food is produced), the weavers bemoan the considerable reduction of grazing pastures, and the pollution especially in the water bodies, that is proving fatally dangerous for the sheep. “About six months ago, a flock of sheep died as they drank the polluted water discharged by a pharmaceutical company. Apart from this, the Nellore sheep was introduced in the region in 1995 for breeding with the Deccani sheep in order to produce more meat. This in turn led to the reduction of Deccani sheep and consequently their wool which is used to make gongadi. Efforts are being made to raise Deccani sheep,” says Yellaih, an artisan and resident of the Medak district.

Australian artist Jo Bertini, who spent six weeks with the pastoralists in different parts of India visiting various communities, says, “I work with camels in the deserts of Australia and with the aboriginal artists. I am here as part of a cross-cultural exchange. Being also an expedition artist who works with scientists in deserts, I find this experience quite interesting. I made a total of 22 paintings both in oil and watercolour. I have painted my work on their handicraft to show their indigenous art.”

Living Lightly is currently on at the IGNCA till 18 December