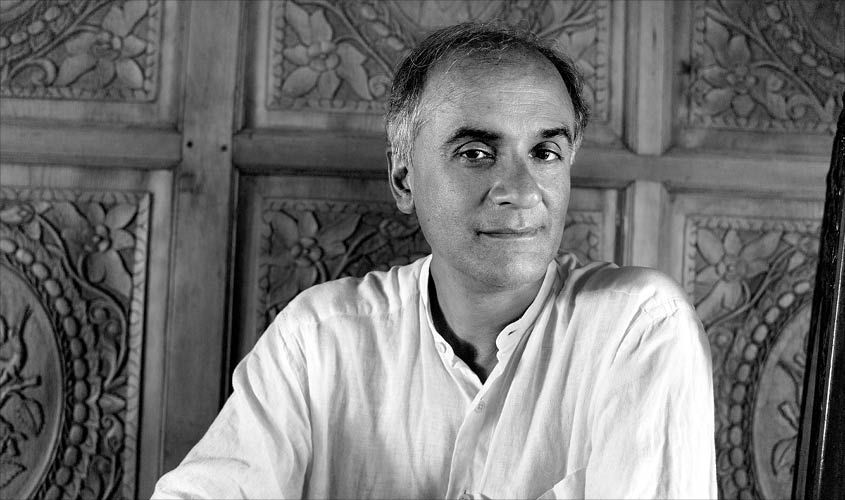

Pico Iyer has spent many years living in Nara, Japan. But there was a time when he was struggling to come to terms with the two seemingly contradictory aspects of Japanese culture—high-tech modernity on the one hand and spiritual depth on the other. His recent book, Autumn Light, is a personal account of how the author came to embrace all the contradictions that Japan had to offer, and how he developed a uniquely Japanese philosophy of life. An excerpt.

It was in autumn that I first got upended by Japan, and realised that not to live here would be to commit myself to a kind of exile for life. I was returning, at the age of 26, to my office in New York City from a business trip to Hong Kong, all high-rising boardrooms and banquets in the casinos of Macao, and my Japan Airlines itinerary called for an overnight layover at Narita Airport, near Tokyo. It was the last thing I wanted; Narita was infamous for 11 years of violent protests by local farmers over the demolition of their rice paddies, culminating in a burning truck sent through the new airport gates not many years before. But I couldn’t argue with flight schedules, and soon I was walking through the high-tech quiet of the arrivals area, and out into a singing autumn afternoon.

A shuttle bus took me to an airport hotel, and an elevator carried me up to my floor. When I got out, the long corridor was so spotless that all I could see was the window at the far end, faraming the first crimson and gold from the surrounding trees. It was hard to tell where the forest ended and the building began.

After breakfast next morning, I still had four hours to kill before check-in, so I followed a sign in the lobby to a free shuttle van into the airport town. Twenty minutes later, I was dropped off on a busy road and crossed a street to find myself in a world suddenly intimate and human-scaled. The streets were barely wide enough for cars here, and many of the houses were made of wood. Panelled doors were pulled back, and, above the tatami mats of tearooms and restaurants, I could see, again, trees beginning to turn, through the picture windows at their back. Everything was silent, deserted, and the mildness of the late-October sky gave a sense of brightness and elegy to the day.

I followed the riddle of streets up to a large gate, which led into a courtyard thick with sweet incense. At the far end sat a wide wooden meditation hall, and all around stood protective statues and what looked to be graves. I didn’t know then that Narita was a celebrated pilgrimage site, consecrated to the god of fire, or that people were known to walk the 46 miles from central Tokyo to pay homage to its thousand years of history; I had no intimation that the Dalai Lama would be visiting months later, and sent his monks here to gain familiarity with the Shingon sect of Buddhism, the esoteric, mystical Japanese school closest to his own.

I simply followed random impulse out into the temple’s garden, where a flock of kindergartners, in pink and blue caps, was scattering across the lawns, collecting fallen leaves. And almost instantly, for no reason I could fathom, I felt I knew the place, better than I knew my apartment in New York City, or the street where I’d grown up. Or maybe it was the feeling I recognised, the mingled pang of wistfulness and buoyancy.

I was so affected—the quiet morning went through me so deeply—that by the time I boarded my plane in early afternoon, I’d decided to leave my comfortable-seeming job in New York City and move to Japan. Four autumns later, I arrived, suitcase in hand, outside the door of a tiny temple along the eastern hills of Kyoto. My boyish plan was to spend a year in a bare room, learning about everything I couldn’t see in Mid-town Manhattan.

That idea lasted precisely a week, which was long enough for me to realise that scrubbing floors and raking leaves before joining two monks crashed out in front of the TV was not quite what my romantic notions had conceived. So I moved to an even smaller room, 75 square feet—no toilet, no telephone, no visible bed— and told myself that in the margins of the world was more room to get lost and come upon fresh inspiration.

Better still, I was back to basics here, with few words to support me and no contacts; my business card and résumé, liberatingly, meant nothing in Japan. Every trip to the grocery store brought some wild surprise, and I barely thought to look at my watch, every day seemed to have so many hours inside it. When, on my third week in the city, I went to Tofukuji, one of Kyoto’s five main centres of Zen, to observe its abbot, Keido Fukushima-roshi, receive initiation into some new level of responsibility, I was placed next to a spirited and charming young mother of two from southern Kyoto whose name was Hiroko. She invited me to her daughter’s fifth-birthday party, five days later, and very soon my year of exploring temple life became a year of watching a new love take flight.

Now, as I step into the post office in Deer’s Slope [a suburb of the Japanese city, Nara], I can hardly recall the bright-eyed kid who made such a pious point of telling himself that purity and kindness and mystery lay inside the temple walls and that everything outside them was profane; the beauty of Japan is to cut through all such divisions, and to remind you that any true grace or compassion is as evident in the convenience store—or at the ping-pong table—as in the bar where two monks are getting heartily drunk over another Hanshin Tigers game.

My trusty protector behind the post-office counter, black waved hair down to her shoulders, flashes me a smile of welcome, and I allow myself to imagine she might be glad of a break after a morning of handling family pension matters. I place the kimono I’m sending to a 10-year-old goddaughter in London on her scales and, long familiar with my clumsiness, she offers to box it up and asks if the little girl would enjoy some pictures of Nara deer on the package. The one time, fatally, I came in during the designated Pico-handler’s lunch break, a much younger woman collected my postcard as if it might be infectious, asked if Singapore was in Europe, hurried back to whisper frantic questions at the coffin-faced boss near the door and ended up charging me four dollars for a stamp.

Now, after buying a 3-D postcard of two bears enjoying green tea in kimono—my mother never can resist such zany pieces of Japan—I head out into the little lane of shops, past the computer store that once placed two white kittens in its windows to attract customers. In the local supermarket, the quiet, pale lady with the sad Vermeer face and braids running down to her waist looks relieved that, for once, I haven’t left a copy of Henry Miller effusions in the photocopy machine. An old man is sitting alone at a small table next to where the mothers are briskly boxing up their groceries, as if waiting for a bridge game to begin. Across the street, the fountain of good cheer at the bakery is bustling around to slice fresh loaves as a soft-voiced woman purrs on the FM station.

Our main park begins less than 200 yards behind the shops, and as I pass the elementary school, I can hear kids chanting, this warm blue day, the 47 syllables of the hiragana alphabet, in the ceremonial song that features every syllable once and once only.

A little like the Anglican hymns we used to sing in school, I think—or the Pledge of Allegiance, which we had to shout out during my brief time in a California classroom.

This song, though, might be the scripture of Japan. “Bright though they are in colour, blossoms fall,” I hear the children shouting out. “Which of us escapes the world of change? We cross the farthest limits of our destiny, and let foolish dreams and illusions all be gone.”

Excerpted with permission from ‘Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells’, by Pico Iyer, published by Penguin Random House