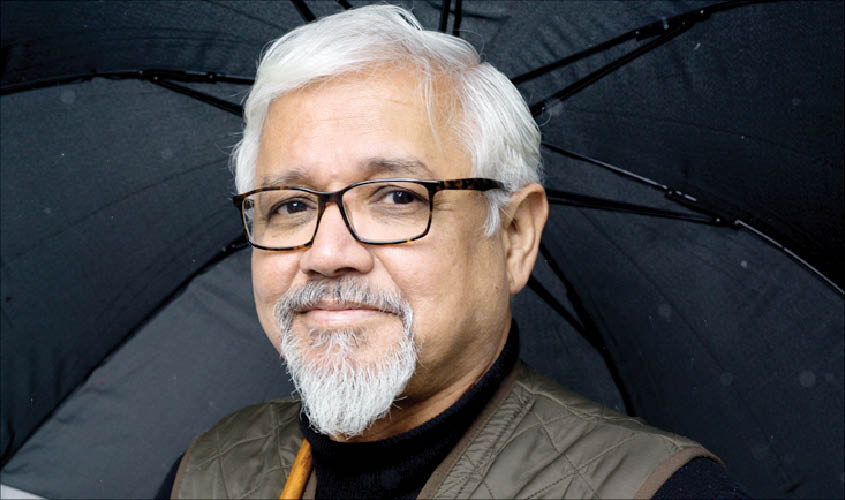

Amitav Ghosh’s latest novel Gun Island straddles the past and the present, while pointing towards an uncertain future shaped by climate change and mass migration. He speaks to Utpal Kumar.

Orhan Pamuk, the 2006 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, writes in his book Other Colours about how some authors are loved for “the beauty of their texts”, which is the purest form of the reader-writer relationship. Other writers, he says, “leave their imprint on us because of their life stories, their passion for writing, or their place in history”.

Amitav Ghosh, the recipient of this year’s Jnanpith Award, belongs to the first group. For, he ardently believes in the purity of the reader-writer relationship, diluted these days by what he calls the eagerness on the part of the writers to become performers. “They [writers] now enjoy being in the public domain all the time. This worries me as it is going to change the very nature of literature,” says Ghosh as he cautions how writing is “no longer about contemplation and solitude.”

Maybe this fascination with being a recluse has helped Ghosh evade the “Rushdiean curse” that often afflicts promising authors who fizzle out after arousing both curiosity and attention in the field of literature. This explains why Salman Rushdie’s best work may still be Midnight’s Children, written almost four decades ago, while every time Ghosh comes up with a new book, a debate resumes about whether it’s his best work or not. From The Shadow Lines to the Ibis trilogy, swords are still drawn among his readers and critics alike. His latest offering, Gun Island, only adds to the allure.

It’s not that Ghosh has created a completely new world in Gun Island. He invokes some of the notable characters of The Hungry Tide—Kanai Dutt, Nilima Bose, Piyali Roy et al—yet it isn’t the sequel of his 2004 book. “Despite having a few common characters in both novels and the Sundarbans forming the geographical bedrock for the two, they don’t have any common ground. In fact, when I started writing Gun Island, I never thought Kanai or Piyali would feature in it. These are two different books and deserve to be seen and read that way,” he says.

Ghosh informs us that Gun Island is about Bonduki Sadagar, a “gun merchant”, who is driven out of Bengal by snake goddess Manasa Devi and forced to take an arduous journey through lands such as Taal Misir Desh (Sugar Candy Land), Rumali Desh (Land of Kerchiefs), Shikol Dweep (Island of Chains) and Bonduk Dwip (Gun Island). These mysterious names hold epistemological clues, with the Italian city of Venice providing the ultimate answer.

Gun Island reads like a thriller, an epistemological one to be precise, as Ghosh lets, one of the book’s characters, Nilima, recite the following lines: “Calcutta has neither people nor houses then/ Bengal’s great port was a city-of-the-world.” It is these two lines that let Dinanath Dutta, the principal protagonist, take a long, arduous journey from the Sundarbans to Venice, searching for the clues, epistemological or otherwise. As Dinanath, commonly called Deen, asks in the book, “Through Arabic the name Venice has travelled far afield, to Persia and parts of India, where to this day guns are known as bundook—which is of course none other than ‘Venice’ or ‘Venetian’… Was it possible that I had completely misunderstood the name ‘Bonduki Sadagar’? Could it be that its meaning was not ‘The Gun Merchant’, as I had thought, but rather, ‘The Merchant who went to Venice’?”

Ghosh agrees etymology has always been at the heart of his books and insists every word has a story of its own. “We have grown up believing that baalti is a quintessentially Indian utensil used for storing water, but the fact is this word has actually come from Portuguese. So is the word mistry, a supposedly desi term for mechanic,” he says.

Coming back to the novel’s plot, Ghosh says, “Spices formed a major part of the Venetian economy and they came primarily from India, especially the Malabar region of Kerala. In fact, the Portuguese and the Spanish famously undertook the voyages of discovery because they wanted to break the Venetian monopoly over spices. Thanks to this flourishing trade, a large number of Indians found themselves in Venice during the medieval times.”

He also explains that things are not very different even now. “I meet so many Bengalis in Venice. So much so that it sometimes feels I am in Bengal, and not in Italy,” says the author.

The book is as much about the past as it is about now and this moment. “Gun Island may talk about myths, merchants and migrations of the past, but its heart lies in the present, especially in the two major challenges being faced by the humanity—climate change and mass migration—and how technology is shaping human responses… We are yet to truly evaluate and appreciate the manner in which technology, especially the smartphone, has disrupted our day-to-day lives. We have grown up hearing that all politics is local, but in the era of such massive technological disruptions, all notions of localism and rootedness seem to have been challenged and defeated,” says Ghosh.

It is this massive technological disruption, he adds, that is creating a new and extreme form of migration. “In the past, after any devastating flood or storm, a person would shift to a nearby village or town, but now, there are no such geographical constraints. A person can now aspire, and even manage, to go to another part of the world, as Tipu’s [a character in Gun Island] own story suggests,” the author says as he goes on to talk about how that “centuries-old project”, which began in the “early days of chattel slavery” and had been essential to the shaping of Europe, “has now been upended”.

The European consensus in the past “to preserve the whiteness of their own metropolitan territories in Europe” is now being challenged and sharply reversed. “The world,” Ghosh writes towards the fag end of the book, “has changed too much, too fast; the systems that were in control now did not obey any human master; they followed their own imperatives, inscrutable as demons.” Is it, therefore, any surprise that in Gun Island, one of the characters (Cinta) tells another (Deen) that the world that we live in now “presents all the symptoms of demonic possession”?

Ghosh invokes climate change to emphasise the chaos and irrationality ruling the world. Echoing Cinta’s statement, the author says that everybody knows what’s the remedy for global warming, and “yet we are powerless… We go about our daily business through habit, as though we were in the grip of forces that have overwhelmed our will; we see shocking and monstrous things happening all around us and we avert our eyes; we surrender ourselves willingly to whatever it is that has us in its power.”

He adds: “Our experiences suggest that we don’t live in a world guided by reason and rational thinking. Had it been the case, we would not have let things, especially on the climate front, on which rests our very existence, go awry so badly.”

The author also makes a strong case for randomness, coincidences and the uncanny. “There’s a scene in Gun Island about a forest fire in Los Angeles. It’s so weird that I wrote this incident in the book six months before it actually happened. But then that’s what life is. If we don›t see something, we shouldn’t deny its existence. Even scientists now leave scope for randomness and the uncanny,” he says. Like Cinta in the book, he adds, “There are many well-documented instances of things that cannot be explained by so-called ‘natural’ causes.”

It’s this sense of randomness and the uncanny that makes Ghosh give voice to non-humans and seek possibilities of what he calls “extraordinary communications”. “Texts in ancient India and even in Greece mention animals speaking to each other and even humans. This was the case till the 19th century, when humans monopolised the discourse. Worse, it’s now not just about humans and non-humans. For there are many marginalised sections among human beings whose voices are never heard. The massacre of lower-caste immigrants at the Marichjhapi island of the Sundarbans in 1979, as depicted in The Hungry Tide, is a case in point.”

A novelist’s greatest virtue, Pamuk once confided, “is his ability to forget the world in the way a child does”. Ghosh, with Gun Island and his other novels, seems to have mastered the art of forgetting the world. And yet he is very much a part of it. He is ever ready to take the magical, uncanny path to peek at the hard realities of life in the world, which is simultaneously real and imaginary, natural and supernatural, beautiful and chaotic. This makes him so irresistible.