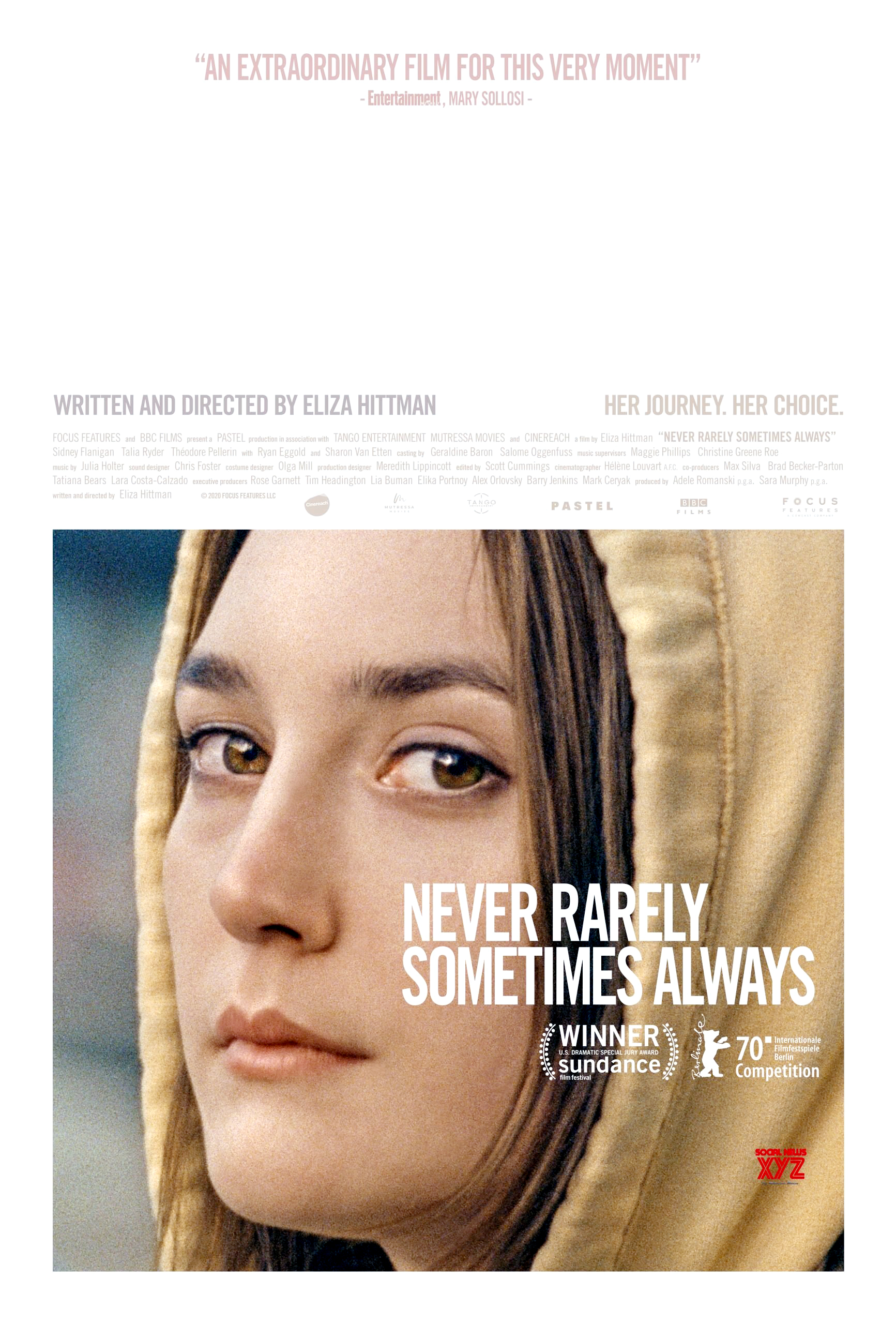

Despite what your brain may tell you, Never Rarely Sometimes Always is not the same movie as Sometimes Always Never. The former (in theaters March 13) is a neorealistic drama that examines the hurdles a 17-year-old Pennsylvania girl faces to get an abortion in New York City. The latter (in theaters April 17) is a whimsical British dramedy starring a Scrabble-obsessed Bill Nighy on a hunt for his estranged son.

Both are small, indie films. Both have spring release dates. And both are eager to find a distinct audience, despite sharing overlapping titles of the same rearranged words.

Yet neither considered changing the title to avoid confusion. Why not?

Writer-director Eliza Hittman originally called Never Rarely Sometimes Always simply A when she began working on the script in 2012. “A as in abortion movie, as in The Scarlet Letter,” she said. “I didn’t think it was a title that would resonate with audiences ultimately, and I knew I was searching for something more dynamic.”

The final title came about through Hittman’s conversations with Planned Parenthood employees and refers to the possible answers to a series of questions that intake counselors ask patients to assess if they’ve been the victims of intimate partner violence. Its meaning is only made clear when it’s spoken repeatedly during a key emotional scene in the film.

“There is something about the repetition of it that really struck me, the rhythm and repetition,” she said. “And obviously, the intimacy of the conversation. I knew in the narrative that we were building to an intimate revelation.”

Never Rarely Sometimes Always premiered in January at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won a special jury award, and Hittman said there was never any pushback on her title choice along the way.

“Obviously, when I was thinking about using it as the title, I did an IMDb search to see if there were any films that shared the same title and nothing came up,” she said, referring to the internet movie database site. She recalled that executives from Focus Features, which is distributing her film, mentioned Sometimes Always Never in an early meeting “but I don’t think anyone felt it would create confusion. It seemed like their film had been made a while ago, so I was a little surprised” to see that it was being released around the same time.

Across the Atlantic, Sometimes Always Never quietly debuted at the 2018 London Film Festival and in several international markets. Its title likewise changed from inception to release.

It was originally called Triple Word Score, like the Frank Cottrell Boyce book it is based on. But legal discussions with Hasbro over the rights to the Scrabble phrase made that a less than ideal choice. And while shooting in 2017, director Carl Hunter felt instantly moved when Nighy spoke the line, Sometimes, always, never, to his on-screen grandson as he taught him the buttoning rule for a three-button suit (top: sometimes, middle: always, bottom: never).

“The title was in the script all the time. We just didn’t spot it,” Hunter said. “Sometimes you read words and they’re great, but then when those words are in the mouth of an artist, all of a sudden they occupy a very different world.”

When he heard Nighy deliver the line, “a shiver went down my spine,” he said, adding, “I thought, ‘That should be the title. It’s philosophical. It’s poignant. And it’s poetic.’”

Hunter’s background as an art director also led him to visualize the phrase on a potential poster. “I look at words very carefully from the point of view of typography,” he said. “To me, I can see those three words, and they occupy a wonderful space.”

Not everyone was on board.

“We had lots of long, hard discussions over whether to change the title,” the producer Roy Boulter said. “There was concern from the marketing department that it wasn’t an easy name to hang onto—Triple Word Score is much easier to remember than Sometimes Always Never. But then you’d get people going into the cinema thinking they’re going to get a Scrabble drama, and that’s not what it’s really about. It just came to the point that it would cause us a lot less hassle with Hasbro.”

While Sometimes Always Never was originally slated for an October 2019 US release, the American distributor, Blue Fox Entertainment, pushed it to March and eventually April to try to find a noncompetitive window. “We are a small English indie and so we’ve got to give ourselves a big chance,” Boulter said. “You only get one go at release.”

Jessica Tabin, a vice president at the Creative Impact marketing agency, said the two movies’ convoluted titles were detrimental—both on their own and in light of their now month-apart release dates.

“Honestly, it’s not like anybody wins, and I’m surprised no one made the change,” said Tabin, whose agency has worked on promotional campaigns for Parasite, The Report and other films. “I really feel like a short concise title always helps. Obviously, not every movie is Lincoln or Goodfellas, so sometimes you have to do a little bit of explaining in your title. But that’s what taglines are for.”

Tabin also noted that it’s not just about what title works when spoken or seen on a poster, but also what makes the most sense when marketing to moviegoers who increasingly find out about films on their phones.

“A really lengthy title isn’t going to play very well on your really small screen if you’re looking through film titles, or for search purposes when you’re looking for movie tickets,” she said.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always and Sometimes Always Never aren’t the only 2020 releases with titles that have wound up playing outsize roles in marketing and reception.

In February, after the Margot Robbie comic-book movie Birds of Prey fell $12 million short of expectations on its domestic opening weekend, Warner Bros. announced a “display change” for the title at theaters and ticketing sites, where it’s now Harley Quinn: Birds of Prey. While the film was technically always titled Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn), Tabin noted that “nobody remembers the parenthetical portions of titles” and many probably didn’t connect the dots that Birds of Prey was “the Harley Quinn film.”

Meanwhile, the title of Autumn de Wilde’s adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma was styled with a period, much to the chagrin of grammar-conscious copy editors. “There’s a period at the end of Emma because it’s a period film,” de Wilde told Radio Times in Britain. (The New York Times opted against using the punctuation for clarity’s sake.)

“A lot of times misplaced punctuation or all lowercase or all caps might stop you in a good way because you’re not used to seeing it,” Tabin said. “It’s there for a reason, and it’s causing you to potentially want to look into it further. And maybe with Never Rarely Sometimes Always, the thought process is it’s so confusing that it catches your eye.”

Ultimately, it’s difficult to gauge how much of a role a movie’s title plays in its box office success or failure, and perhaps the parallel appellations of Never Rarely Sometimes Always and Sometimes Always Never will even work in their favor.

“Whether it worries me or not, I’m not quite sure,” the Sometimes Always Never director Hunter said. “In a strange way, because of Eliza’s film having a similar title, the phone has been ringing and people want to talk. So maybe, actually, it’s a very good thing.”

© 2020 The New York Times

The curious case of the strangely similar movie titles

- Advertisement -