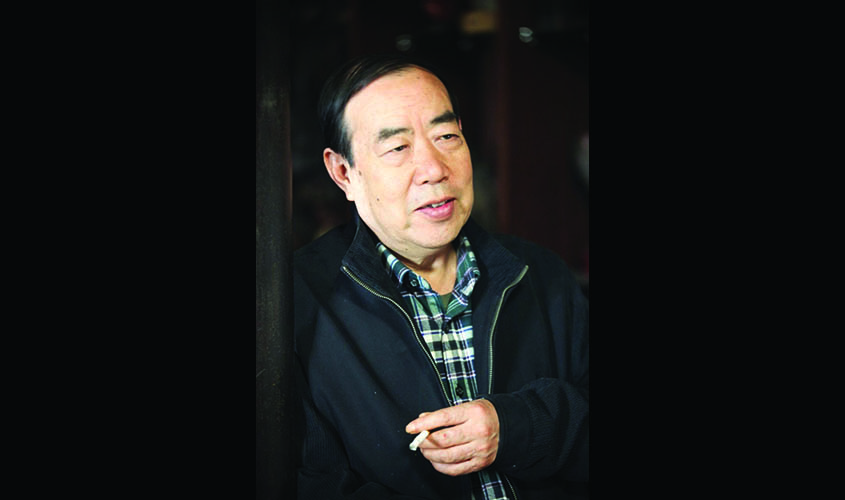

Chinese author Jia Pingwa, recipient of the Mao Dun Literature Prize, the highest literary honour in China, speaks to Latha Srinivasan about life under censorship, and finding a global audience.

Jia Pingwa is one of the most renowned authors in China but his life as a writer hasn’t been easy. The 2009 Mao Dun Literature Prize winner has seen the Cultural Revolution in China, and the numerous political turmoils in the country since. Pingwa’s famous 1993 book Ruined City was banned for 17 years by the state administration but he never gave up writing about the common people. In 2017, his book Happy Dreams was translated by Nicky Harman, and today, the world is Pingwa’s oasis. In this exclusive interview with Guardian 20, Pingwa talks about his books, life and more.

Q. You were born in Dihua village and moved to Xi’an later to study and work. Happy Dreams is about Happy Liu who comes from the rural area to Xi’an. How much of this book is autobiographical?

A. I came from a small village. I am quite familiar with everything in the countryside. Of course, some of the thoughts and mental activities of the rural migrant workers came from my own experience. However, the character of Happy Liu is the reflection of one of my primary-school mates.

Q. What kind of aspirations did you have when you moved from your village to the city? Did you believe a better life was possible and you could achieve it?

A. When I moved to the city, the entire living environment had changed tremendously. I was very confident then that a very promising life lay right there ahead of me.

Q. Where did your desire to become a writer stem from? Was it thanks to the political climate in the 1960s?

A. My other surviving skills are terrible compared to writing. I’ve got a feeling that I have talent in writing, so I developed myself into an author.

Q. Once a pariah, you are now hailed by the establishment in China as an important voice. How much of this matters to you?

A. This change made me feel the important purpose and value of my life; I could now speak to the world and utter my own voice.

Q. You write a lot about the common people. Why is that?

A. The main purpose of my works is to let other people know the daily life of Chinese people, their living status and mental life.

Q. Your novel Feidu was banned for 17 years because of the topic it dealt with. Why did you choose to write about sex? And how did you feel when it was unbanned and published with edits?

A. The sex plot in Feidu (Ruined City) is designed for the main character. Zhuang Zhidie, the protagonist, fell into the arms of women when he was in agony; he even tried to save these women but instead, he ruined them and himself. There’s an ancient Chinese poem: “Grasp the sword and strike the water, while the water still flows. Raise the cup to drown one’s grief, while grief only grows.”

I think it best describes the story that happened to Zhuang Zhidie. Of course, I was quite happy when the book was unbanned. After all, Chinese society has leapt forward, people’s mindsets changed, now they’re able to view the novel from a purely literary perspective.

Q. Times have changed in China since the 1960s. Are you more comfortable as a writer there today?

A. Yes, they have. However, the creation of literary fiction gets harder and harder. Readers now have better taste and this in return pushes the writer to improve themselves and make breakthroughs.

Q. You’ve won many literary awards. Which one is the closest to your heart?

A. Regarding the awards in China, of course, it is The Mao Dun Literature Award. [Mao Dun Literature Award is the highest literary honour in China.]

Q. With your novels getting translated into English, you have a worldwide audience now. Does this put more pressure on you as a writer?

A. A writer will always feel pressure. Of course, the translation means I’ve got more readers, which is a form of encouragement for me as well.

The author’s responses, originally in Chinese, were translated into English by Nicky Harman