A salient aspect of Krishna Rajya is its emphasis on the need for a strong, centralised state, but one based on the tenets of good governance and ethical polity.

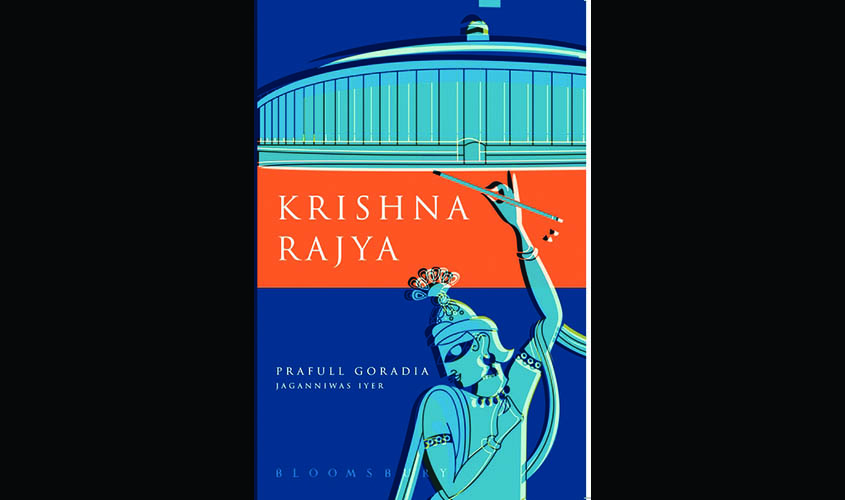

Krishna Rajya by Prafull Goradia and Jaganniwas Iyer

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Price: Rs 699

New Delhi: As far as characters from the ancient or hoary past go, Krishna, one would say, has been one of the most written about and discussed. There is a plethora of literature on Krishna, straddling his multi-faceted persona of boy wonder, mischievous son, steadfast friend, butter thief, companion of the gopis, friend and philosopher of the Pandavas and above all, the one who gave the world the timeless Bhagavad Gita. How is Krishna Rajya, written by Prafull Goradia and Jaganniwas Iyer, published by Bloomsbury India, different?

In the book’s introduction, the authors explain why they have chosen Krishna as the central subject in a study of polity, with strong emphasis on how a state ought to be administered and what its relations vis-à-vis other states are. The incisive foreword by Dr Koenraad Elst, a renowned Belgian Indologist and internationally acclaimed scholar, too is an exceptionally lucid exposition on why Krishna is to be studied as an exemplar of state-building. Prafull Goradia, a former Member of Parliament (he was a BJP MP in the Rajya Sabha during the tenure of the Atal Behari Vajpayee government) and one of the two authors explains in “Why this Book?” his reason for choosing Krishna. Krishna Vasudeva, explains Goradia, not only underscored the need for a unified state, but strove to create a unified India, and made unhesitating and often remorseless use of realpolitik to realise his aim. Interestingly, Goradia also says—drawing from his own experience as a politician and parliamentarian—that his realisation is that India can be governed effectively only by an Indian system, and not by one that has been built with imported bricks and is unsuited to India’s ethos. Goradia perhaps alludes to the current Indian Constitution, which is largely based on Government of India Act of 1935, which is a product of British India. In his quest for an Indian system and polity, the author says that his mind first dwelt on Rama and then on Krishna.

The reason for choosing Krishna might come as a surprise to most Indians, who, though familiar with Krishna’s persona as a Ras Lila adolescent, a flute-playing cowherd and later Pandava warrior Arjuna’s friend, philosopher and guide, are oblivious of his much more versatile avatar as a general, a military thinker, a political strategist, a diplomat and so on. Krishna Rajya not only brings out all these facets in generous detail, but underlines a hitherto untouched aspect of Krishna’s life—of being one of India’s earliest political unifiers. This might come as a surprise to most readers and also invite derision from those accustomed, out of their ideological volition, to being dismissive of ancient India’s history as myth. But the historicity of Krishna is more or less a given. Ideological arraignment to the contrary therefore, ought to be treated more as polemics, and more often than not, an agenda-driven exercise. As Dr Elst explains in the book’s foreword, the strictest application of academic rigour will yield the inescapable conclusion that of all major civilisations in the world, the Hindu vision of India as a single land and cultural entity, remains the oldest, and has found undeniable expression in myriad ways, irrespective of what today’s secularists might like to pretend or believe.

Krishna Rajya’s authors have chosen to highlight, after much research on the subject, this aspect of Krishna’s life and mission. It is revealing to read how India battled political fragmentation as well as external threats and armed invasions. The authors, through their treatment of the then prevailing political circumstances, have been successful in bringing out how Vasudeva Krishna not only resolutely battled the perils and those seeking to erase dharma from society, but also how he dealt with external enemies who sought to destroy the Indian way of life. Then, as of now, there was no dearth of opportunist and adharmic Indian rulers who had no qualms in making common cause with aliens to fulfil own ambitions. In Krishna’s lifetime, the evil but powerful Jarasandha of Magadha menaced a substantial part of India, while a powerful Greek invader Kalyavana threatened to extinguish dharma and the Indian way of life. It is safe to say that Krishna’s defeat and eventual destruction of the twin threats that menaced India that is Bharat, have not received the study they merit. Even less known is his strategic leadership in freeing India’s western regions from the stranglehold of competing civilisations: Krishna and his people had to fight the Phoenicians, Assyrians, Sumerians and Babylonians to wrest control of what is today’s Saurashtra in Gujarat. His flight to Dwaraka along with the Yadavas in search of safety from imperial Magadha is no mere legend, but a historical fact, bolstered by adequate references. It is understandable that these events of Krishna’s life have remained obscured in the dazzle of his divinity. The influence of the Bhakti age on Indian society is preponderant over political and strategic thinking.

A particularly salient aspect of the book is its emphasis on the need for a strong, centralised state, but one based on the tenets of good governance and ethical polity, exactly what Krishna strove for throughout his sojourn on earth. Juxtaposed against Rama Rajya, which remains the Indian ideal for a just and benign state, Krishna Rajya—a concept authors Goradia and Iyer have introduced for the first time—is a treatise of a realist state. The authors have drawn out parallels elsewhere in the ancient and modern world, namely in ancient Greece, in which Plato’s classic Republic lays down the need for and nature of a state; in 20th century American scholar Hans Morgenthau’s vision of a realist state based on ethical values; in the historic endeavours of the iron-willed Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck in unifying the fragmented Germanic principalities into a single state; in 19th century American President Abraham Lincoln’s struggle and supreme sacrifice to keep the United States united; and in India’s iron man Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s still unsung saga of defeating nefarious forces and unifying India politically. The distinction of what a dharmic state, which does not mean a religious one, and an adharmic one, has been suitably explained in the form of two contrasting models. Krishna Rajya therefore, merits being called an experiment on India-based political science; one cannot think of many such efforts. Kautilya’s Arthashastra was perhaps India’s first major treatise on political science, and that was written some 25 centuries ago. As the authors have mentioned, India has an enormous treasure of philosophy beginning with the Rg Veda. Because of the several millennia of its life and the size of the subcontinent, Indian history is vast. Philosophy and history are the parents of political science. It, therefore, remains a wonder why they have not produced more offspring. Krishna Rajya is an endeavour in that direction.

One may argue, and not without justification, that the book has not devoted enough space to explaining the nature of dharma and particularly Krishna’s vision of dharma, for that was what he strove for. There might well be ample merit in this criticism. Yet, the authors have not been entirely oblivious on this score. They have eschewed legend and focused on Krishna the versatile colossus. Krishna’s own abstinence from the temptation of power, in not allowing his own community the Yadavas to become the central pole in India’s polity, but empowering the virtuous Pandavas instead, are the manifestation of his vision of impartial dharma. India’s experience in the post-Krishna ages, under the Mauryas, Sungas, the Guptas and Harshavardhana, is pertinent. Only a strong state could repel invasion; the fragmentation thereafter laid open the country to alien intrusions. Krishna Rajya reinforces the message in an unmistakable way.

Aswini K. Ray is a retired -professor of the Jawaharlal -Nehru University.