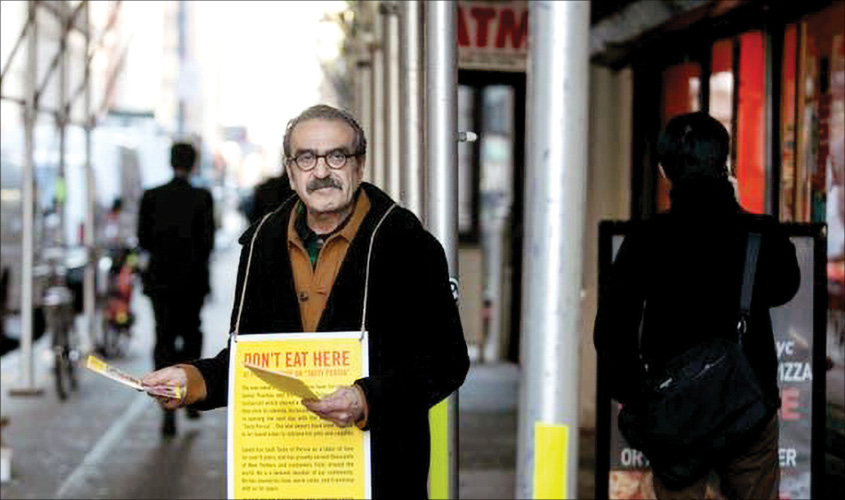

Trouble had come to Pizza Paradise. A police car sat outside 12 W. 18th St. on Monday. Two protesters paced the sidewalk, bearing saffron-yellow placards and handing out fliers printed with an all-caps battle cry: “DON’T EAT HERE.”

Inside, two police officers conferred with the pizzeria owners. Solo diners hunched over triangles of pepperoni.

The counters to the left of the front door were bare—a conspicuous blank spot in a city where every inch of real estate is exploited and fought over. For seven years, that corner belonged to one of Manhattan’s most charming and serendipitous pop-up restaurants: Taste of Persia NYC.

There, Saeed Pourkay, a print-shop manager turned chef, stocked chafing dishes and pots with the likes of fesenjan, a stew of crushed walnuts and pomegranate molasses, sour and sweet. His ash reshteh, a dense noodle and bean soup, was simmered for hours down to a heavy ink and topped with bronzed shards of garlic, crispy onions, dried mint and a cooling daub of sour kashk (fermented whey).

Although the New York metropolitan area is home to the second-largest population of Iranian descent (more than 32,000 people) in the United States, there are only a few Persian restaurants in the city. Pourkay, who left Tehran in 1978 during the Iranian Revolution, was a beneficent figure in the Flatiron district, doling out samples of stews in tiny spoons, eager to share his cuisine with those merely in search of a New York slice. His lines grew long.

Then, in November, new owners took over the pizzeria. They quarreled over his share of the rent—he paid $900 a week for his corner, contributing about a quarter of the owners’ total monthly payment—and asked him to leave.

To be a New Yorker is to live in constant mourning. One by one, the places we love are taken from us, often by rising costs.

But that’s not why Pourkay, 66, was protesting outside the pizzeria. He had accepted his fate, he said, and cleared out his space last Friday as promised. He thought he had parted with the owners on good terms, trading hugs and kisses. But when he returned Sunday to pick up equipment and food he’d left behind, he found a new sign posted in what was once his window.

Tasty Persia NYC, it said.

It was deep crimson, just like his old sign. A Persian rug hung on the wall. New chafing dishes gleamed. On the menu were his old favorites: ash reshteh, bamieh (okra) and kaleh gonjeshki (tiny meatballs, literally translated as “sparrow heads”).

Pourkay suspected a plot to push him out, replicate his business and profit from the reputation he’d worked years to build. He confronted Thogan Magableh, one of the pizzeria owners.

What happened next is in dispute. Things got physical. Both parties called the police, and Pourkay was barred from the premises.

Shortly after, he posted a video online that showed him weeping in front of the pizzeria, saying, “He stole everything.” Former customers started flooding Facebook and Yelp with negative reviews of Pizza Paradise. A GoFundMe campaign, set up by fans on Pourkay’s behalf, has raised more than $22,000 to help him open his own place.

On Monday, his pizzeria window was empty, as if neither Taste of Persia nor Tasty Persia ever was. Magableh, an immigrant from Jordan, told me he would no longer serve Persian cuisine.

Still, his son, Sam Magableh, insisted that they had done nothing wrong. His mother, who is Persian, cooked the dishes, he said. “You tell me I can’t sell Persian food?” he asked.

“In the Middle East we all eat like this,” the older Magableh added. How was it Pourkay’s food?

When I reviewed Taste of Persia in 2013 for the Hungry City column, I noted that Pourkay had to cook in the off-hours, when the pizzeria kitchen wasn’t in use. Sometimes he came in as early as 1:30 a.m. “This hardly seems a sustainable state of affairs,” I wrote.

Apparently Thogan Magableh didn’t think so, either. He proposed a 50-50 split of rent and expenses, after tallying up the cost of extra electricity and gas from Pourkay’s hours of cooking, and of his staff’s having to stay late to clean and lock up. (People don’t dawdle over slices, but Persian food, rich and fragrant, encourages lingering, even in the glare of a no-frills dining room. )

Pourkay said this offer was made not to him directly, but to his younger brother Vahid Pourkay, who runs a long-standing print shop a few blocks away. It’s an old-school way of doing business, family to family.

His brother laughed off the offer: “Half the rent for that 10-by-10 place?”

Now the brothers stood together on the sidewalk, politely flagging down passersby. The fliers were the handiwork of Vahid Pourkay’s print shop. As the saying goes, never pick a fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel.

“The police told us we could be here so long as we don’t block the door,” Saeed Pourkay said. He was supposed to fly to Iran later this week, for a long-deferred vacation, but canceled the trip.

The landlord has agreed to help Pourkay retrieve his remaining equipment. In the meantime, Pourkay is working with a pro-bono lawyer to prepare a suit alleging intellectual property theft. He says he will continue to protest.

“I kissed them, I hugged them,” he said, remembering his last night with the pizzeria owners. “I have to protect myself.”

© 2019 The New York Times