BJP MP says that people in charge of making decisions for cities often do not understand the struggles citizens face.

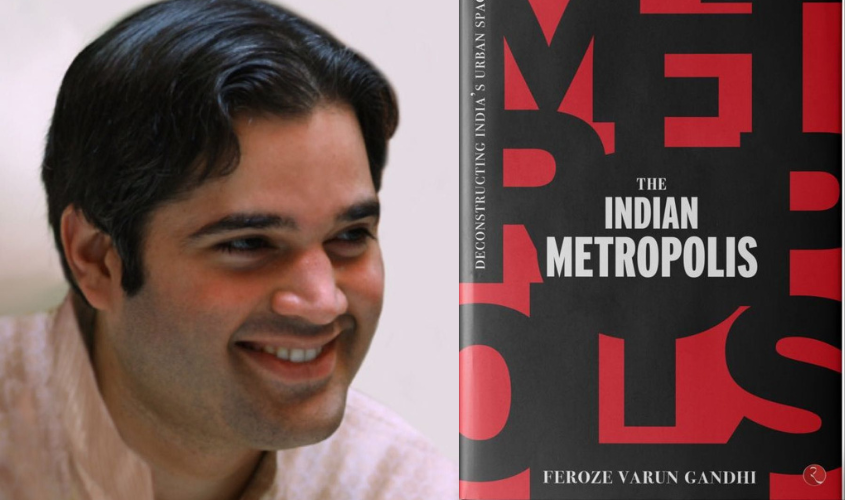

NEW DELHI: A three-time BJP MP from Uttar Pradesh’s Pilibhit constituency, Varun Gandhi is not just a politician, but a writer and poet as well. While his first book was on the rural areas of India and its challenges, his recently released book “The Indian Metropolis” takes a look at the problems of urban India. Gandhi said that it took him “three tumultuous years” to write the book as he has taken a deep dive into the complexities of the problems of urban India and suggested solutions for them. On the event of his book release, Varun Gandhi spoke to The Sunday Guardian on his book and the experience through the journey of his writing. Edited excerpts:

Q: Congratulations on your new book, this time it is on urban areas. The last book you wrote was on rural areas. What prompted you to write this book?

A: After spending almost half-a-decade understanding and discussing the travails of rural India, the idea of writing on how Indians live in urban India was a tall order. As I interacted with thousands of Indians living in our cities and recovering from the pandemic, I understood, life in cities in India is tough for many people. It’s difficult for those earning around Rs 10,000 to Rs 15,000 a month to pay for a house to live, buy food and groceries, and brave the daily commute, especially during extreme weather conditions. People in charge of making decisions for cities often don’t understand the struggles its citizens face, and as a result, cities are becoming unaffordable and hard to live in. Additionally, cities are losing touch with India’s cultural heritage and moving away from sustainable practices. We need to have a national discussion about these issues as a country.

Q: In the book, you have stressed on the need to “rethink’ how cities should be managed and how local governments are often playing catch-up as it is unable to provide infrastructure. What according to you are the key issues that need immediate attention? Are the state governments and the Centre doing enough to make urban areas future ready?

A: India’s cities are facing a number of challenges related to urban planning and the impact of climate change. Mumbai and Gurugram, for example, sink from annual flooding due to heavy monsoonal rains. Bengaluru and Hyderabad are facing the issue of vanishing local lakes and Delhi is witnessing rising encroachment of the Yamuna floodplain areas due to increased infrastructure projects. With the increasing frequency of high intensity rainfall, Indian cities will continue to be affected. Bad urban planning, combined with climate change, will mean that Indian cities are perennially besieged.

To address these issues, a different model of urbanization is needed. India needs to prioritize economic integration within its cities, improve transportation options, and shift towards affordable housing. Currently, the focus

Breaking up large cities into smaller units, if necessary, can improve governance and create better living conditions for citizens. This will help ensure that cities are able to provide a hospitable environment for everyone, with a focus on improving quality of life and making public services more accessible and affordable for all. Addressing these issues is crucial for creating liveable and sustainable cities in India.

Q: The Centre has launched various schemes like AMRUT, PMAY-Urban, Smart Cities Mission etc, to create or upgrade urban infrastructure. Do you think these schemes have delivered the desired result?

A: Over the past decade, there have been notable investments in urban infrastructure as well as healthcare, food provision, education and other areas. However, India’s urban challenges are vast in nature and much remains to be done. From annual flooding in the monsoons, to lake frothing, garbage fires, India’s urban governance has chaos writ large. Over 55% of our urban citizens live in cities where a mayor has had a term of 2.5 years or less; meanwhile, only 13% of all cities have enacted town and country planning acts post the liberalization era. Just 2 cities have actually bothered to create ward committees and area sabhas. Over half of India’s cities do not generate enough revenue to meet salary costs, despite limited growth in municipal staff over the past decade, and a significant ongoing vacancy.

Q: The Centre recently announced the setting up of an Urban Infrastructure Development Fund, on the lines of RIDF, for developing urban infrastructure in tier-2 and tier-3 cities for which Rs 10,000 crore will be given annually. Your previous book was about rural India. What’s your take on RIDF and the newly announced fund? Do you think the newly announced fund will benefit tier-2 and tier 3 cities?

A: It is heartening to hear the Centre push for the creation of Urban Infrastructure Development Fund. The modalities of funds and its remit are in the process of being set up; it would be premature to comment on it before it has had a chance to make a mark.

However, much more needs to be done to bridge the gap in funding for India’s municipalities that is seeing fiscal stress. A multi-pronged strategy is needed, including providing fiscal stimulus, a revolving fund, and green bonds. Property taxes need to be rationalized and expenditure efficiency increased through outsourcing and PPP models. Concessions should also be rationalized and integration with other government schemes, such as the Smart City Mission, should be explored. Overall, the aim should be to improve the fiscal situation of urban local bodies and municipal corporations while boosting public health and supporting the local real estate market.

Q: In the book you mention that broadening MGNREGA to an urban locale is “most natural extension”. Please elaborate.

A: The idea of an urban employment guarantee scheme is one whose time has come. There are murmurs already: in 2019, in Madhya Pradesh, the government initiated the “Yuva Swabhiman Yojana”, which offers employment to skilled and unskilled workers. Kerala, since 2010, has run an initiative (termed as “Ayyankali Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme” which offers 100 days of wage-employment to urban households in return for manual work.

The Supreme Court has also acknowledged the importance of such a scheme, recognizing the “right to life” in the constitution as not just a right to exist, but also a right to livelihood and dignity. MGNREGA, which provides a “right to work” in rural areas, broadening this to an urban locale is the most natural extension for the Indian state.

Combining the urban employment guarantee scheme with efforts to create green jobs can also improve India’s urban landscape. We need to consider a pan-India scheme (with an initial pilot scale) for an urban version on a job guarantee scheme, covering 100 days of work, at Rs 500 per day (to be validated across all urban agglomerations), in all Tier 1, 2 and 3 cities, as well as census towns. This scheme would seek to cover 4,000 such towns with 126 million people of working age. This would focus on ensuring that workers, across education levels, would be offered 100 days of guaranteed employment a year. Such urban citizens would be deployed on a range of tasks–building, maintaining streets, footpaths, bridges, tunnels, etc. In addition, focus on “green public works” (e.g. creating, restoring, and maintaining urban common spaces) would create sustainable public assets.

Q: Will this not add to the burden on the exchequer?

A: For funding such a programme, my book highlights a variety of examples and financing options. Green bonds need to be pursued with gusto, along with a joint corpus fund, funded by the Centre and states. Property taxes also are fit for rationalization, to stimulate the local real estate market – it will be important to raise the share of registered urban residences which pay property tax–tools like GIS mapping, along with cross-checking with other identification databases could help bridge this gap. Concessions will need to be rationalized, with state and local bodies incentivised to move away from fiscally ruinous measures (for e.g. offering water or electricity for free to urban citizens). Expenditure efficiency will also need to be boosted, by pushing for outsourcing (e.g. for garbage services) and exploring PPP models (e.g. hybrid annuity models), and participatory budgeting.

Q: Your previous book was on the rural areas and the new one is on urban areas. How much will both of them help the dispensation to formulate policy for Indian villages and metro cities?

A: After spending almost half a decade understanding and discussing the travails of rural India, the idea of writing a dense synthesis of facts and personal anecdotes on how Indians live in urban India was always a tall order. We need more empathy for the bedevilled urban Indian and the marginal farmer, helping to shape policy choices that improve their lives and alleviate hardships, while setting up the infrastructure to further growth and build climate resilience. This book hopes, through a series of vignettes, to elucidate answers to such queries, with their constraints and potential solutions. It hopes to highlight experiences from my decades-long public life, serving as an MP and a stakeholder for mostly rural and urban constituencies, while drawing lessons from sociological experts and development policy.

Q: With your writings, you have established yourself in a different league of politicians. Do you think you have been duly rewarded for your exceptional leadership qualities?

A: Imbibing this tome’s themes has left me with a greater appreciation for the challenges that our municipal administrators, urban policymakers and leaders face, as they seek to shape our cities. I have travelled far and wide, across a multitude of Indian towns and cities, listening to the ordinary urban Indian’s everyday stories, and admiring the dignity with which they face the daily struggle. Pushing to solve their daily pain points is a far greater aspiration for me than any personal reward.