The book opens new vistas into the actor’s life, telling with anecdotal details how he was destined to be a star. He must be celebrated for what he was and has been.

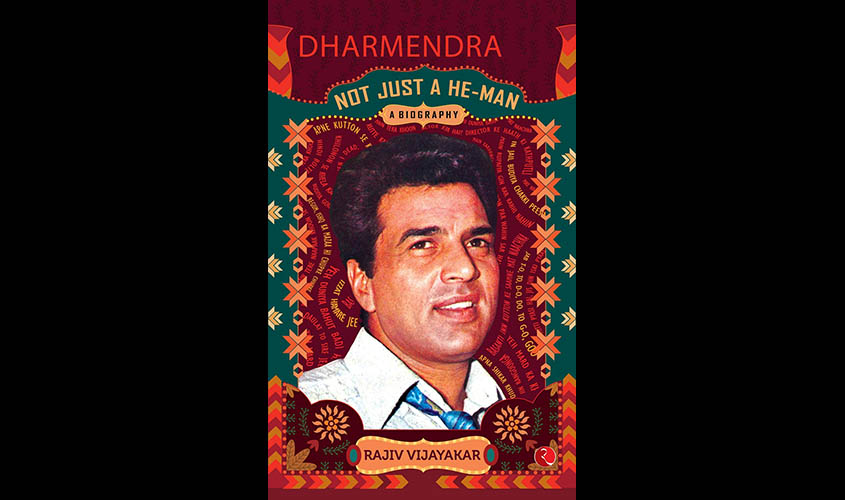

Dharmendra: Not Just a He-Man

Author: Rajiv Vijayakar

Publisher: Rupa

Price: Rs 595

In her heydays, or one should say heady days, between the late 1930s and the early 1950s, Hedy Lamarr, a Hollywood actress known for exceptional beauty, starred in over two dozen films. She would sometimes be singled out for work, but her good looks were invariably and universally praised. “My face has been my misfortune,” she wrote in her 1966 memoirs, Ecstasy and Me. “My face is a mask I cannot remove. I must always live with it. I curse it.” Lamarr thought people failed to see her skills, acting and otherwise (the actor shared with composer George Antheil a patent issued in 1942 for inventing a technological system still used in military communications), just because they found her beautiful.

In Hindi cinema, if Mukul Kesavan is to be believed, Dharmendra faced a similar, Lamarr-ian dilemma, thanks to his good looks “in a conventional North Indian way”. His Greek God looks seemed to have masked the actor in him. So much so that Dharmendra, discovered in a Filmfare talent spotting competition at Mehboob Studio in 1961 by the legendary Bimal Roy and Guru Dutt, failed to win a single Filmfare Best Actor award despite having worked in about 300 films. Yes, he got the Filmfare Lifetime Achievement award in 1997, but the magazine didn’t find any of his individual performances worth “the Lady in Black” despite his legendary Veeru, Parimal and Satyapriya roles, to just name a few! As noted film writer Gautam Chintamani writes in one of his tributes to Dharmendra, “One of the most enduring mysteries of Hindi cinema is the manner in which it chose to sideline an actor and a superstar such as Dharmendra, who unlike many of his contemporaries could don a dhoti with the same ease with which he could sport a Roman Toga, he could be smoldering in a tuxedo and set a million hearts ablaze in a bundi and could make you laugh, sigh, cry without making a big deal of it.”

With Dharmendra getting a new biography in Rajiv Vijayakar’s book, Dharmendra: Not Just a He-Man, one hopes we would finally have a definite, conclusive answer on why he failed to achieve the stardom he so genuinely deserved. Or, is it that we failed him in getting what was rightfully his? The book opens new vistas into the actor’s life, telling with anecdotal details how he was destined to be a star. “Years ago, he (Dharmendra) had gone with his uncle for a relative’s wedding to a nearby town. He was about 12 or 13 years old at the time, studying in Class VIII, when he got to watch (the result of a promise made by the uncle as an incentive to attend the wedding) a film called Shaheed at the Minerva cinema in Ludhiana.” The Dilip Kumar-starrer had a great impact on the young Dharam and cinema became his true and only obsession.

Dharmendra was soon in Bombay. During his initial struggles, he found a friend in Manoj Kumar, whom he called “Manno”. Both were then struggling to get a break in Bollywood. Vijayakar recounts how at o ne point Dharmendra was so disillusioned and disgruntled that he decided to leave Bombay for “a job in Dhaka Colony” in New Delhi. “Wait for two months—I will look after all your expenses,” Kumar assured. And just two days later, muhurats for two films—Picnic and Shola Aur Shabnam—took place. Both Dharmendra and Kumar had lead roles in the two films. Ironically, in their long filmy career, as the fate would have it, they could never work together as leads.

Vijayakar explains that Dharmendra lost Picnic because he contracted jaundice and lost a lot of weight which made him unsuitable for the role of an Army officer. As for Shola Aur Shabnam, this time Kumar lost out. He had unfortunately confided the story of the film in his struggling actor-friend, M Rajan, who managed to get the role earmarked for Kumar through his producer brother. “And the two friends lost both the chances of coming together in a film,” writes the author.

The book has more such interesting anecdotes, from Dharmendra accidentally getting inside the bedroom of his idol, Dilip Kumar, during his struggling days, and rushing out riotously when the latter screamed to see a stranger in his house, to Dev Anand, another of his icon, one day coming over to him when he was standing in a queue for some audition and telling him out of the blue: “You will make it!” Dev Anand chatted briefly and even gave Dharmendra cold water from his ice-box.

The strength of the book is that it doesn’t pass any judgement. It just tells stories surrounding the Deols through their eyes, and the eyes of their friends and colleagues. But the book’s strength is its weakness, too. One, it doesn’t explain why Dharmendra could become such a big star in the first place; he was among very few who could successfully withstand the Rajesh Khanna tsunami between 1969 and 1973. And, two, despite such a range of films, from Anupama and Satyakam to Sholay and Chupke Chupke, how could his entire legacy get confined to being the He-Man? Was it his failure of imagination, or has the Bollywood failed him?

The book may not give these answers but, to the credit of the author, it does provide enough hints through anecdotal tales. Here’s one from the book when Guru Dutt was suddenly called to attend a court case just before the finale of the Filmfare talent contest. Dharmendra was selected among six others. Abrar Alvi, Dutt’s friend and writer, was told to conduct the test with instructions to “check the contestants’ faces, profiles and dialogue delivery from the filmmaker”. When Dutt returned, Alvi informed him about Dharmendra “who had a crew cut, while everyone else had long hair, modelled broadly on Dev Anand’s style”. When Dutt asked him who he was like in terms of acting style, Alvi said matter-of-factly: “Nobody! He is himself, has no pretensions, no set notions. The boy seems an original and it might be possible to mould him and develop his personality.”

It is this originality of Dharmendra that made him stand out. For, he belonged to the era when every new actor was seen aping one of the famous trio—Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand. If Rajendra Kumar was trying to get into Dilip Kumar’s shoes, Manoj Kumar attempted to combine a Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor into his acts, and Shammi Kapoor took on the Dev Anand mannerisms. Dharmendra was among the very few, and definitely the best among them, who wanted to be his own. And this explains why he could pull off the dhoti-clad Satyapriya in Satyakam and the bare-chested Shaka in Phool Aur Patthar so effortlessly. He was the first superstar who wasn’t bound by an image.

But then how could the image of He-Man get attached to him? Vijayakar believes it might be Dharmendra’s revenge on the viewers for the failure of Satyakam, a film he not just acted but also produced. But, for every failure of Satyapriya, there was the success of Parimal. The answer, probably, lies with the persona of the actor. If the ever-simpleton Jat in Dharmendra endeared him to us, this very happy-go-lucky persona also led to his marginalisation. Till the time the industry was dominated by Bengali filmmakers like Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Pramod Chakravorty and Shakti Samanta, he gave rousing performances, but when the nature of Hindi cinema changed, things turned awry for him. Dharmendra, with his star power, could have changed things. But the simpleton in him, with the ego and stubbornness that comes with his extreme rootedness, didn’t allow him to go that far. It just told him to go with the flow, and the Bollywood’s flow in the 1980s was in favour of B-grade action films.

What if Dharmendra had reached out to the likes of Yash Chopra (from whose Waqt he opted out), Manmohan Desai (with whom he had a fallout after he refused to do Amar Akbar Anthony) and Prakash Mehra (whose Zanjeer he was supposed to act in)? Had he done that, maybe he would have done some better films in the 1980s and ’90s. But would he have remained the star we so endearingly love? Maybe that’s the bargain Dharmendra made to remain true to his roots, close to the masses. Maybe that’s what makes him so popular till date. Dharmendra must be celebrated for what he was and has been, not what he could have been.