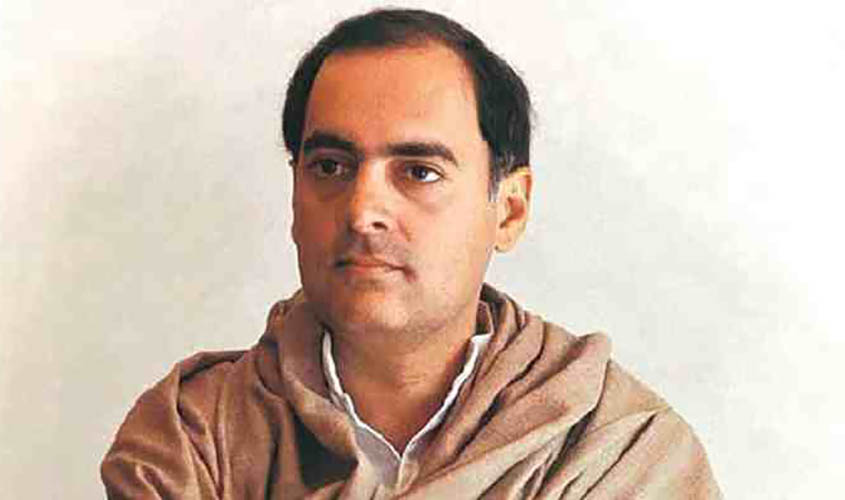

Rajiv Gandhi was a charismatic personality. However, what was equally undeniable was the under-performance during his 1984-89 stint as Prime Minister. There were indeed some green 21st century shoots emerging from the muddy field of policy, such as in telecommunications or panchayati raj. Credit for the first goes to Satyen Pitroda, who anticipated the telecom revolution which followed two decades later. Rajiv made some use of Pitroda, but not enough to make an overall difference, such as by inducting him into the Union Cabinet or ensuring that the bureaucracy was kept away from the telecom sector. That last has yet to happen. Indeed, the babus are firmly in the driver’s seat. The electorate had overwhelmingly supported Rajiv Gandhi in 1984, less out of sympathy than hope that this youthful leader would ensure change. However, soon after he took charge, officials steeped in the past closed in around Rajiv, blocking him off from the outside world so far as policy formulation was concerned. Satyen Pitroda was an exception. Mani Shankar Aiyar was another exception, and had he been given executive powers to devolve authority to the lower administrative units, the country may have been transformed.

Rajiv Gandhi was a charismatic personality. However, what was equally undeniable was the under-performance during his 1984-89 stint as Prime Minister. There were indeed some green 21st century shoots emerging from the muddy field of policy, such as in telecommunications or panchayati raj. Credit for the first goes to Satyen Pitroda, who anticipated the telecom revolution which followed two decades later. Rajiv made some use of Pitroda, but not enough to make an overall difference, such as by inducting him into the Union Cabinet or ensuring that the bureaucracy was kept away from the telecom sector. That last has yet to happen. Indeed, the babus are firmly in the driver’s seat. The electorate had overwhelmingly supported Rajiv Gandhi in 1984, less out of sympathy than hope that this youthful leader would ensure change. However, soon after he took charge, officials steeped in the past closed in around Rajiv, blocking him off from the outside world so far as policy formulation was concerned. Satyen Pitroda was an exception. Mani Shankar Aiyar was another exception, and had he been given executive powers to devolve authority to the lower administrative units, the country may have been transformed.

Rajiv Gandhi soon learnt to be comfortable with the bureaucracy, and largely functioned in the groove dug out for him by them. As for his ministerial team, most were chosen for their caste or closeness to those interests seen as vital to the kind of politics that has long been the norm in India. Rajiv’s spinmeisters created a hostage to the future by painting Rajiv as “Mr Clean”, in a context where the monetary expenses of doing politics were rising exponentially. It was during the time that middle-rung party functionaries regarded stay in 4-star hotels, travel by air and the ownership of flashy cars as being the essentials of democracy. In 1989, the Congress Party lost despite its resources, not simply because the economy was still too shackled to the constraints of the 1970s, but because Rajiv Gandhi too often bowed to 19th century minds, as over Shah Bano. Rajiv continued the policy of appeasement of fundamentalists by giving weightage only to the views of fringe elements in the Muslim community, and ignoring the fact that the overwhelming majority of Muslims in India are as moderate and progressive as any other community.

Rajiv Gandhi, early in his political debut, understood the need to ensure the crafting of a governance matrix that reflected the needs and aspirations of the present, rather than the colonial past. A visitor to his 1 Akbar Road office during 1981 and the most part of 1982 would see scientists, writers and thinkers being escorted to an honoured place in the living room, while politicians even of ministerial rank milled around in a back portico, drenched in sweat. However, by the close of 1982, Arun Nehru became the key adviser to the AICC general secretary. Nehru focused on the immediate future, sometimes ensuring quick results, but in ways that created longer-term problems. Slowly, independent voices lost their access to Rajiv Gandhi. Much of the time of the Heir Apparent was spent with those who had, for decades, been prominent in the party, and who were averse to the changes that Rajiv had earlier vowed to bring about. More and more, he began to follow the line urged on him by the party satraps, adopting boilerplate solutions to new problems rather than fresh approaches.

Later, the same post-1982 tendency of going by conventional un-wisdom continued during his stint as Prime Minister. Not that flashes of the pre-1983 Rajiv were entirely absent. For example, as PM he went ahead with what could have been path-breaking peace initiatives in Punjab and the Northeast, but which fizzled out at the last mile because of over-reliance in implementation on the same bureaucratic machinery that had allowed such problems to fester for so long. The result was that the core of the problems remained, breaking out again and overcoming the beneficial effects to the periphery of the concerned issue that had been tackled by the move. A policy is only as good as its “last mile”, or at its point of delivery, and it is here that Rajiv’s complacent dependence on an unreformed bureaucracy worked against the changes he sought. Comfortable in the official cocoon wrapped around his every move, he refused to accept that no surgeon can conduct a successful operation with obsolescent instruments.

Had Rajiv Gandhi used the considerable goodwill that was his for the asking till mid-1986 in going through with administrative reforms on the same scale as, for example, seen in the UK during the 1980s, even the Bofors scandal would not have felled him. Voters expect politicians to collect money. They know that few elections are won by saints. What they seek from their leaders is a visibly better life with hope for still more improvement in the future. By the close of 1986, the hope that Rajiv would be a transformational leader was almost extinguished. This lowered his political resistance sufficiently to enable the first major scandal, that of the Swedish gun, to deny him success in 1989.

In 1947, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Deputy Prime Minister Vallabhbhai Patel and other Congress leaders adopted the democratic (i.e. Homeland British) model of politics, throwing away the colonial construct that had so diminished India the previous century. Why they retained the colonial construct of administration rather than adopt the democratic version of governance implemented within the UK itself was as incomprehensible as it was tragic. Hence the contradiction between a democratic Constitution of India and a hyper-colonial Indian Penal Code. Why the founders of the republic failed to factor in the contradiction between a democratic model of the polity and a colonial model of administration is a question that historians committed to acting as public relations agents for Nehru have not bothered to examine. The country’s politicians, who almost entirely focused narrowly on immediate political needs rather than empower citizens in the race towards a Middle Income India, acted in tandem with the official practitioners of colonial governance to ensure that the promise offered by Rajiv Gandhi to the electorate in 1984 remained that. A promise unfinished, a vow unfulfilled.