China didn’t start bullying in 2020, but it has certainly upped its game of “coercive diplomacy”. Records show that China has bullied more countries this year than in the previous ten years combined. Any criticism of China produces an immediate reaction from Beijing, frequently leading to wild words of contempt and economic boycotts. President Xi Jinping has made it perfectly clear that he is weaponising the global dependence on its huge economy, a stance which could quickly lead to a new “economic cold war”. China’s form of coercive diplomacy isn’t well understood by many countries, which are consequently struggling to develop an effective toolkit to push back against it. China bullies because currently it gets away with it.

There were early signs of coercive diplomacy back in 2010, even before Emperor Xi ascended the throne, when on 8 October the Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize to the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo. There was an immediate reaction from Beijing, declaring the award to be a “big mistake” and that it would have “damaging consequences for Sino-Norwegian relations”, even though Norway emphasised the independence of the Nobel Committee. In Xi’s mind there is no such thing as a committee “independent” of the State. Within three days, bilateral free-trade negotiations were called off, quickly followed by trade and travel restrictions imposed on the Norwegians by Beijing. Somewhat cynically, this didn’t stop a Chinese State company from buying a Norwegian hydro-company at the height of the tensions—the company’s expertise was critical in China’s exploration of the South China Sea.

In 2016, South Korea announced the purchase and installation of the US Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) system to focus on threats from South Korea, an ally of China. A few days later the Chinese Foreign Ministry released a statement expressing its “strong dissatisfaction and firm opposition” to the deployment, which again was quickly followed by trade and tourism restrictions. The state-owned media spearheaded a campaign against the South Korean car manufacturers Kia and Hyundai, resulting in a drop in sales of 52%. Images of a Hyundai vehicle being vandalised by an angry mob in China went viral on the internet in March 2017.

A year later, Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer and daughter of its founder Ren Wanzhou, was detained and arrested in Canada, following a request for extradition by the US. There was an instant reaction by Beijing and two Canadian tourists were charged and arrested for “espionage”. Another Canadian, who earlier had been arrested in China on drugs charges, had his jail sentence changed to the death penalty. Again, Beijing imposed trade restrictions, but this time in a more subtle manner. In March 2019, Chinese authorities banned all imports of Canadian canola, a vegetable oil based on a variety of rapeseed used as a stock-feed, falsely citing “harmful organisms” found in the crop. Two months later, China suspended all meat products from Canada, using the spurious claim that Canadian meat exporters had “forged” certificates.

All of this, however, pales into insignificance when compared to China’s current malicious bullying of Australia. The trigger for the bullying was a perfectly reasonable and sensible call in April by Australia’s Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, for an independent international assessment of how the coronavirus pandemic had occurred, so that lessons could be learned to prevent it from happening again. At the time, the coronavirus had infected 3 million and killed 200,000 people worldwide. It had also shut down the global economy.

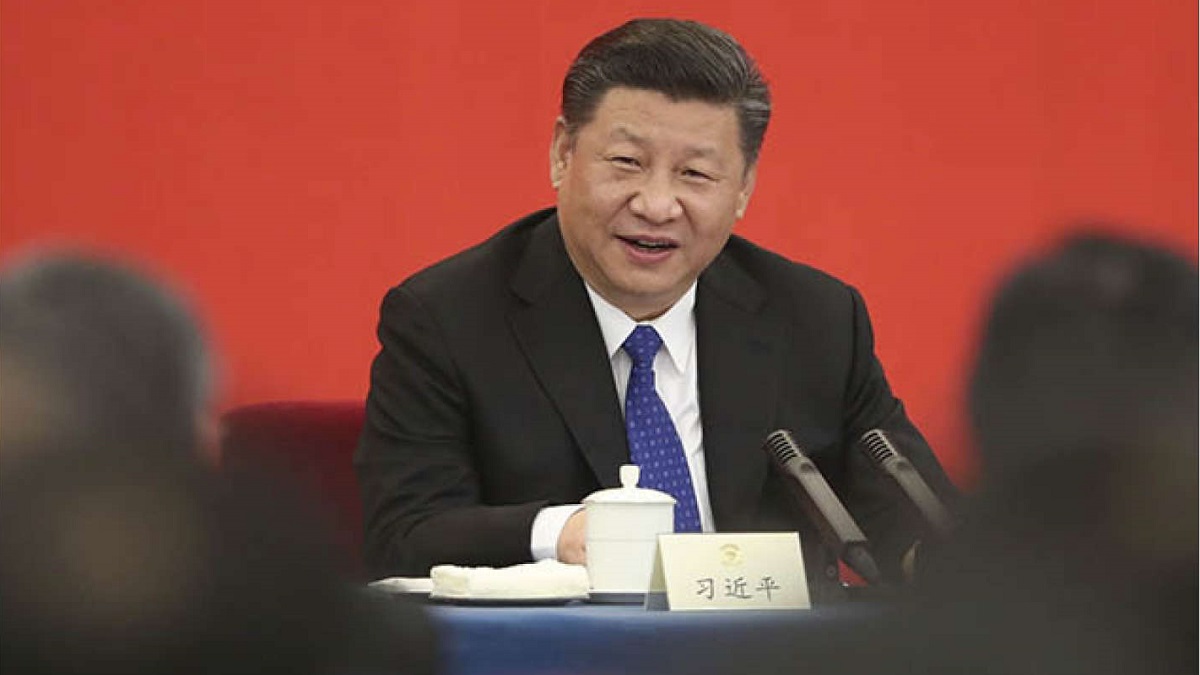

Morrison had clearly touched a sensitive nerve in Beijing and while he could have predicted that Xi Jinping might be a little annoyed by his statement, neither he nor anyone foresaw the subsequent explosion and intensity of anger from China. Refuting any blame for the pandemic, Chinese state media was incandescent and ran strings of inflammatory statements and insults, accusing Australia of “panda bashing” and calling the country “gum stuck to the bottom of China’s shoe”. “Australia is doing the work of the US but without holding any influence”, claimed an editorial in the Beijing propaganda mouthpiece, the Global Times, accusing Australia of “risking long-term damage to its bilateral relationship and trading partnership”. Morrison politely responded that Australia’s relationship was “mutually beneficial” and noted that its trade with China consisted mainly of export of resources; “I see no reason why that would alter in the future”. How wrong he was. Eight months on, the economic fall-out has been ginormous.

The curious thing was that previously, the Australian government had gone out of its way to praise Beijing. Their ministers had duly regurgitated Chinese Communist Party talking points, such as praising the country’s achievement in lifting millions out of poverty. As a sign of friendship the government had even invited President Xi Jinping to address their Parliament in 2014. China had also become Australia’s largest trading partner, accounting for $120 billion (33%) of its exports. But as trade built up, Australia, like other liberal democracies, became increasingly challenged by the need to balance its economic dependence on China with its own values and interests. Morrison’s mild comments on the coronavirus were in this vein; but they were not the first.

Australia’s attitude to China had started to shift after Beijing began to interfere in its political system. In response, Australia’s Parliament enacted new laws in 2018 to criminalise foreign interference and limit foreign donations to political parties. Also at that time, the Australian media exposed the brazen reach of the Chinese authorities to hunt down Chinese nationals abroad whom Xi Jinping had seen as threats to his autocratic regime. Beijing had used the cover of the phony anti-corruption drive, “Operation Foxhunt”, which not only led to extensive surveillance throughout Australian universities, but also had become a huge threat to the large Chinese diaspora in the country, especially ethnic Uyghurs.

China’s immediate response was to arrest Australian citizens and slap tariffs on Australian exports, starting with beef and barley. In the aftermath of Morrison’s remarks, these were followed by a huge increase in tariffs on Australian wine (China is the number one export market for Australian wine worth $870 million per year), Australian lobsters (90% of the catch goes to China), coal, barley, copper ore, sugar and timber. Beijing’s bullying reached new heights last month when the Chinese Embassy in Canberra leaked a dossier of “14 grievances” to several Australian news outlets in an attempt to humiliate the country. The list was almost amusingly exhaustive, insisting that Australia rescind not only the call for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19, but also its criticism of human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and the reversal of the ban of Huawei from the country’s 5G network.

China’s continued attack on Australia is unprecedented, but Xi Jinping clearly sees the country as a soft target because of its economic dependence on China. By attacking Australia, Xi has calculated that China will face few, if any repercussions and usefully send an important example to the rest of the world: “If you criticise China, this will happen to you”.

Many Australians are worried by these developments. But China’s bullying of Canada and South Korea hasn’t forced these countries to capitulate so far, and there’s no reason to believe that they’ll work any better in Australia. On the contrary, many business leaders will conclude that future hedging of their business will be necessary to avoid the “China treatment” should politics get in the way of commerce. While any decoupling from supply chains linked to China could carry significant short-term economic costs, particularly during the current pandemic, the public humiliation experienced by Australia will make compromise and future cooperation difficult, if not impossible. The argument for diversifying export markets and supply chains away from China will become more and more persuasive as companies see massive tariffs slapped on their products without notice simply because of their government’s critical comments about Beijing’s bullying behaviour.

This, of course, will not be easy and in the short term the tempting solution will be to find a form of compromise. But there is a limit to how much humiliation any country will accept and China’s brutality could well backfire. Beijing appears to be unaware or unconcerned by the recent Pew poll which showed that “unfavourable” views of China have reached record highs in many countries. In Australia, for example, the current figure is a massive 81%, an increase of 24% in the past year. Across the 14 countries surveyed by Pew, China is viewed negatively in every case, the most being in Japan (86%). The obvious conclusion is that unless China changes its ways and curtails its behaviour, coercive diplomacy could turn to its disadvantage. There will be no binary moment when countries switch from engagement to decoupling, but this will surely happen over time as China’s current trade partners diversify their supply lines.

The year 2020 is, of course, designated the Year of the Rat in the Chinese Zodiac, which today seems somehow appropriate. Just as rats were believed to have carried the Black Death across the world from China in the 14th century, China ratted on the world in 2020 by infecting it with the coronavirus. Next year will be the Chinese Year of the Ox, but take a look at the symbol they use for an ox—indistinguishable from a bull. So it’s in the stars that China will carry on bullying countries that have the audacity to criticise it. Hatred of China will become a pandemic in 2021, and Emperor Xi will soon learn that his bullying will come with costs.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998.