Given our natural predilection for the deviant and the unusual, a movie on Sanjay Dutt was anyway due.

T^he Ranbir Kapoor-starrer Sanju has disturbed the Rashtriya Sevak Sangh, which has questioned the “intent” of the biopic. In fact, its members went on to question the very need to make movies on criminals and gangsters. “On whose direction is this happening? Is money from the Gulf (West Asia) behind this?” asked Panchjanya, the official mouthpiece of the RSS. Is there pressure from the underworld, it wanted to know.

Well, one can’t answer for sure, but there need not be any pressure or conspiracy by the mafia. Production of such films could be happening because of a very simple reason: vice has a much bigger market than virtue in the world of cinema. And it’s not just in our country, but across the globe. For a Mangal Pandey, a hundred scoundrels have been portrayed on the celluloid in our country; and for A Beautiful Mind, a 2001 American biographical film based on the life of Nobel laureate John Nash, a thousand movies have been made on criminals.

So, the problem is perhaps not with the likes of Rajkumar Hirani and Vidhu Vonod Chopra, the filmmakers of Sanju, but with us, the people. We are more interested in the lives and times of criminals, psychopaths, felons, crooks, etc., than in the strivings and struggles of saints, scientists, philosophers, and philanthropists. Of course, the alternative explanation trotted out by some is that such films are a conspiracy of cosmic proportions by some evil global syndicate that goads, coaxes, or finances filmmakers all over the world to focus on sin and downplay saintliness.

What seems more likely is that we are more interested in the deviant rather than the standard, in the unusual rather than the usual, in the abnormal rather than the normal. The normal is, to many anyway, boring. Who wants to know about the regular, good man who takes care of his wife and children, pays taxes regularly, abides by laws (even when these are awful), and goes to Vaishno Devi? But everybody would be interested in knowing the guy who takes care of somebody else’s wife, cheats the government, and visits places respectable men shouldn’t.

Similarly, who is interested in the good woman who prepares breakfast and lunch for her husband and children, chaperons the latter to the school bus, busies herself in household chores, and observes Ekadashi and Navratra fasts? But everybody—at any rate, every man—is interested in the woman who prepares dinner for a man other than her husband, indulges in non-sanskari activities, cracks dirty jokes, and likes to experiment in the bedroom.

It’s not just cinema but also literature that is enriched by irregular men and women. Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence is regarded as a classic, but it is the story of an adulteress. The protagonists of Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert and Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy are also married ladies involved in extramarital affairs. Therefore, movies on these great novels can also be accused of glamorising, if not promoting, adultery. Emile Zola’s heroine in Nana is actually about a prostitute. Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind is not promiscuous, but she certainly is neither a paragon of perfection nor an exemplar of feminine virtue as conventionally understood. And in a democracy, such portrayals are a commonplace, given public tastes

In India too, litterateurs have shown more interest in the wayward than in the standard. Agyeya’s Shekhar: Ek Jivani has shades of an incestuous relationship. Premchand’s Nirmala also has a similar hint. Bimal Mitra’s Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, on which a great Hindi film was also made, is all about the decadence of feudalism, complete with mentions of debauchery and profligacy. And then there is Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas, on which innumerable movies have been made.

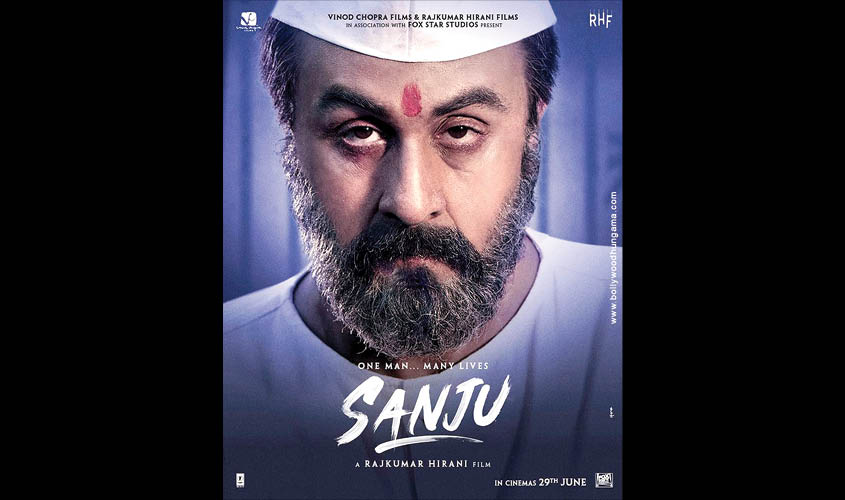

Given our natural predilection for the deviant and the unusual, a movie on Sanjay Dutt was anyway due. He has had a rollercoaster of a life: celebrity parents, drug addiction, rehabilitation, the arms case, the incarceration, a successful film career, marriages, women, et al.

The only thing I find objectionable about the film is that Sanju is still active; ideally, such films should be made on people after they hang their boots. But if Dutt is fine with a biopic on him and producers are willing to do that, it’s all right by the rules of freedom of choice. Therefore, the saffron brotherhood should not worry about any conspiracy or foreign hand. It looks like the filmmakers wanted to make money; and they have succeeded. Just as, as Freud supposedly said, “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar,” sometimes a movie is just a movie.