The so-called ‘Wolf Warrior Diplomacy’ did not originate in China, as the exact same phenomenon emerged in Russia a couple of decades ago.

A political joke circulated in Russia in 2007, and a review of it today reveals a chilling degree of accuracy. The joke was to this effect: Putin and Medvedev were privately discussing a problem. Medvedev said: “We have to win the right to host the 2014 Winter Olympics. The economy is booming, oil prices are rising, your targeted poverty rate has dropped from 30% to 13%, we even won the European Song Contest in your honour.” Putin listened, nodded his head, and then declared that this means “we must now win World War III.”

The Medvedev-Putin tandemocracy was the joint leadership of Russia when Vladimir Putin—who was Constitutionally barred from serving a third consecutive term as President of Russia—assumed the role of Prime Minister under President Dmitry Medvedev. While the office of Prime Minister is nominally the subservient position, Putin was the de facto leader during this period, with most opinion being either that Putin remained paramount or that he and Medvedev had similar levels of power. Putin was re-elected President in the 2012 election and Medvedev became his Prime Minister.

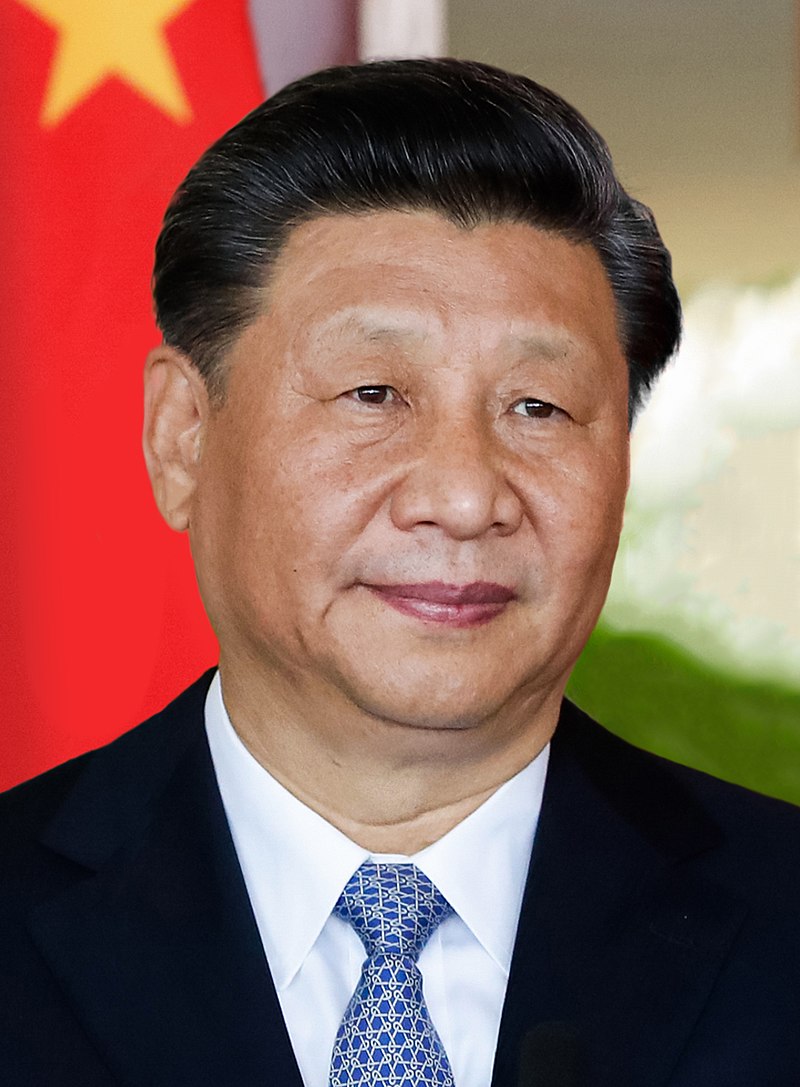

This joke makes one tremble with fear because 15 years later, Putin actually launched his invasion of Ukraine, which may have triggered World War III. It was just a joke at the beginning, indicating that the Russian people at the time saw Putin’s wild ambition, but did not think that he would really go to war, otherwise it would not have passed as a joke. However, what the Russians did not dare to imagine has become reality today. Another interesting aspect of this joke is that if you replace the characters in the joke with a conversation between Xi Jinping and his cronies, and apply it to the political situation in China today, you will find that there is actually no inconsistency at all, even specific details such as the Winter Olympics and poverty eradication can be applied to the same joke in Russia in 2007 and China in 2012.

This, in fact, is an issue very much worth reflecting on.

This political joke comes from the book “Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell In and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin” (Yale University Press, 2014) by Ben Judah, former Reuters correspondent in Moscow. I would like to earnestly recommend it to those who are interested in the development of Russia and China, because reading it today can give us a very important reminder: the development trajectory of China today is, to a large extent, a replication of the development trajectory of the Russian model after Putin came to power in 2000. And the degree of replication can be said in many respects to be slavish imitation, with little significant difference. If we see and agree on this, then we will have an important reference for predicting China’s future development path.

The book provides a lot of evidence to support the above statement. For example, the author states: “In the 2000s, the Russian economy stabilized, and the increase in oil production and prices brought wealth to Russia. A new middle class emerged, Russia became a consumer society, and people traveled abroad in large numbers. Russians, who were becoming wealthier, lost interest in politics, and even rejected it. Putin’s dictatorship seemed to be far away and irrelevant to them.” I believe that everyone can see that the overall state of social development in China today is almost exactly the same as in Russia during that period.

The next and more striking similarity is that the so-called “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy” did not originate in China, as the exact same phenomenon emerged in Russia a couple of decades ago. From the perspective of foreign policy actors, the author says, economic self confidence coincides with a change in self perception. Moscow embraced the Brazil, Russia, India, and China [BRIC] emerging economy label, and began to see itself as an emerging power. Moscow’s foreign policy discussions began to focus on anticipating a prolonged recession in the West, and on how to restore Russia’s influence among the former Soviet states. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov began to mention that he believed the days of Western superiority were numbered. This is reminiscent of China’s rhetoric in recent years about the “rising East and declining West,” and the emergence of “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy.” In an even more striking parallel, it was around the time when Russia began to become more assertive that “influential politicians began to ask Putin to ‘follow United States’ President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s lead’ and amend the Constitution to run for a third term as President.” And “Putin began to change.”

Here we can see that the changes that have taken place in China since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, as well as the changes that have taken place in Xi Jinping himself, are almost identical. More importantly, the logic that led to such changes is also the same: economic growth boosts a ruler’s confidence, confidence gives rise to the expansion of naked ambition, while society ignores or tries to ignore political regression because of economic stability. The final result is that a globalizing society slowly regresses back to a monarchical model without realising it.

The similarity of paths between Russia and China is obviously not a historical coincidence. There is a lot of logic behind the systemic factors, which in itself is a topic worthy of study. However, I would like to emphasise that a careful study of the development of Russia and Putin after the year 2000 will help us understand and predict the past transformations and future direction of China and Xi Jinping.

Wang Dan was born in Beijing in 1969. After entering Peking University in 1987, he was a politically active student in the history department, organizing “Democracy Salons” at his school. When he participated in the student movement that led to the 1989 pro-democracy protests, he joined the movement’s organizing body as the representative from Peking University. As a result, after the June 3-4 massacre, he immediately became the “most wanted” on the list of 21 fugitives issued. Wang went into hiding but was arrested on July 2 the same year, and sentenced to four years’ imprisonment in 1991. After being released on parole in 1993, he continued to write publicly (to publications outside of mainland China) and was re-arrested in 1995 for conspiring to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party and was sentenced in 1996 to 11 years. However, he was released early and exiled to the United States. Wang resumed his university studies, starting school at Harvard University in 1998 and completing his Master’s in East Asian history in 2001 and a PhD in 2008. He also performed research on the development of democracy in Taiwan at Oxford University in 2009. From August 2009 to February 2010, Wang taught cross-strait history at Taiwan’s National Chengchi University as a visiting scholar. He then taught at National Tsing Hua University until 2015. He is now the director of the Dialogue China think tank.

Translated from Chinese by Scott Savit.