Nehru made freedom of speech conditional on the will of the bureaucracy.

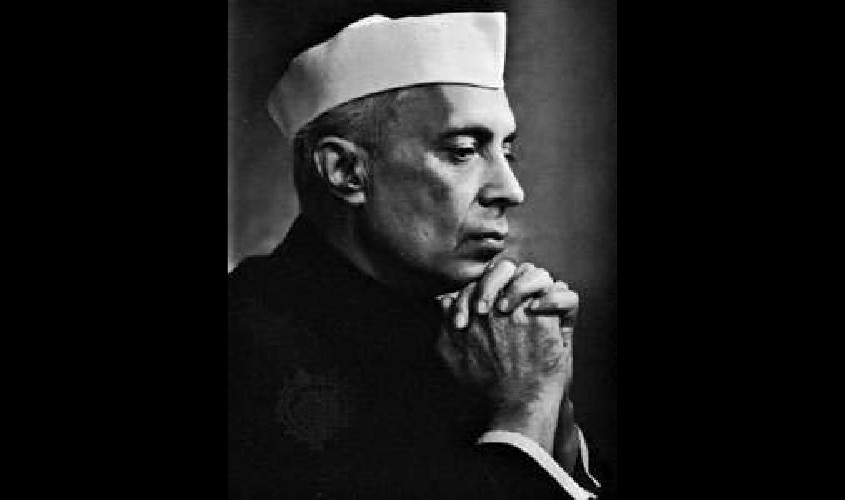

In a democracy, governments cannot be equated with the people. During British rule, any effort against that government was treated as an attack on India and punished, as though the “nation” comprised only of the British. It took only 16 months before the Constitution of India was amended to ensure that the maxim of “Government equals the Nation” once again took effect in jurisprudence. Mao Zedong brought together into a single country more territory than China had effectively controlled throughout its long history, while those who led India after the British left accepted a cruelly truncated subcontinent with merely a rhetorical shrug (“not wholly or in full measure but very substantially”). Abraham Lincoln waged war on the seceding states that formed the Confederacy in order to keep the country united, while Nehru was horrified at even the thought of bringing together what had been torn to pieces. Tripurdaman Singh has written a book on the first amendment to the Constitution of India, an episode which merits inclusion in school and university syllabi. The book, Sixteen Stormy Days, narrates the methodical way in which Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru overturned the freedoms that had been guaranteed to the people of India by the foundational document that had been unanimously approved by the Constituent Assembly just 16 months earlier. Freedom of speech was made conditional on the will of the bureaucracy, while lapsed British-era powers of the state to take away the wealth and liberty of the citizen were reinstated. Sections 124A and 153A of the Indian Penal Code were brought back into life, while Article 15 assuring equality of every citizen before the law had several exceptions tacked on to it. The government was in effect identified as the nation, which meant that criticism of the government was tantamount to an attack on the state. And as Jawaharlal Nehru in actuality was the government, criticism of the Prime Minister was treated as anti-state and anti-national. Once the First Amendment to the Constitution got passed in 1951, the colonial overlay of the governance mechanism regained its supremacy, a dominance that it has since never lost, despite 73 years after “freedom”. To this day, the civil service has mastery over civil society much the way it did during the days of British rule. It seems futile to expect any ruler of the country to divest the government of colonial-era powers that are routinely utilised, but until this happens, the country can never move into the stable double digit trajectory that is needed to be societally stable and economically prosperous. A persisting colonial mindset seeks to enforce a uniformity across the country that is destructive of innovation and enterprise. There was once an expectation that technology, in the form of an expansion of high-speed bandwidth across the country (coupled with a reduction in the costs of access) would create an ecosystem in which new knowledge-based industries would be set up and thrive. Instead, the three branches of the state have, over the course of a decade, ensured that the telecom sector in India has been denuded of almost all of the players who at different times entered it. It now consists of just three enterprises, two of which are in the ICU, while the other is just barely in a state of health, despite repeated doses of vitamin shots. Given the broadband and telecom morass in the country, it is difficult to fathom where those who sought to achieve a miracle and convert India’s economy from cash to (digitally enabled) cards in an instant acquired the optimism which caused them to carry out in 2016 a demonetisation of the currency unprecedented both in scope and effect anywhere in the world and anytime in history.

In this era, where jail time is the fate of many who are less than respectful to those in authority, it needs to be remembered that such a trend began during the very first years of freedom. Given the curbs to freedom of expression caused by the First Amendment, was it any wonder that textbooks and the media soon got filled with encomiums to Nehru? Or that nascent efforts at examining the causes and legacy of Partition were soon replaced with the government-approved version of events, which was that the vivisection was inevitable and indeed, desirable? The government got back the licence it enjoyed during the colonial period to curtail multiple freedoms of citizens on the grounds of “public interest” (where the well-connected constituted the “public”). The only individual who had the will and the stature to stand up to Nehru—Vallabhbhai Patel—died towards the close of 1950, and from then onwards, Nehru began to insert the government into the daily lives of citizens so as to denude them of rights, including liberty and property. Security of property is essential to rapid development