It will cost the exchequer Rs 6 lakh crore to finance the NYAY scheme for the targeted 5 crore families.

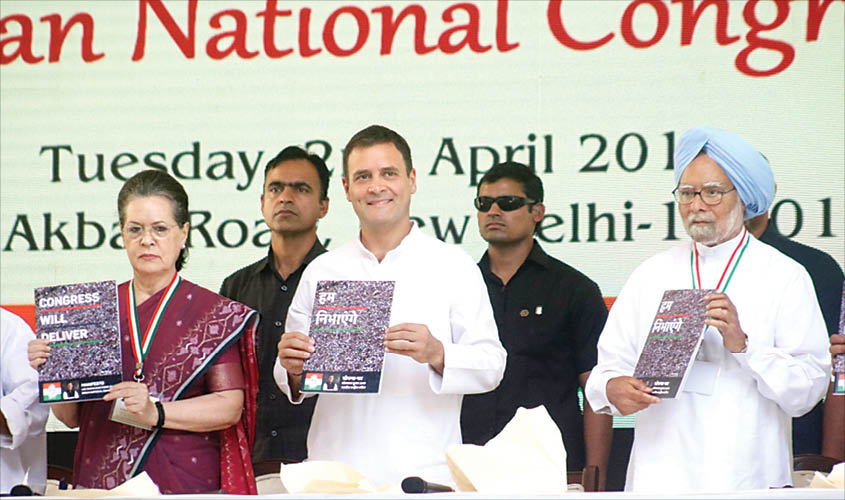

The Congress party in its daring manifesto just before the do or die election of 2019 has released its version of the universal basic income model (UBI) or NYAY, which it promises to deliver if it were to come to power. While the concept is not new and dates back to 1795, when it was proposed by a small group of magistrates in Speenhamland, England while trying to find a solution for the steep rise in the price of grain, which had begun to affect even the employed, leading to a rise in poverty levels.

The magistrates came up with a solution of providing measured help as means to top up to cover the cost of living. The calculations at the time were based on the number of loaves of bread the assistance would provide. The Speenhamland system, also known as the Berkshire Bread Act, was a radical move for the times and was seen as a form of external relief targeted to alleviate rural poverty in England and Wales towards the end and the beginning of the 18th and the 19th centuries. The law was an amendment to the Elizabethan Poor Law. With the Speenhamland system in place, a family with three children could buy more than 25 pounds of bread a week with the top up money or living wage by working little or not at all. This model took over much of England and by the time of the Napoleonic wars it was seen a method to allay the brewing discontent amongst the growing number of rural poor affected by the skyrocketing food prices. The Speenhamland system came to an end by 1834. The system which had started at the municipal levels had failed to achieve a national consensus and become law. The critiques of the system were none other than the leading classical economists of the time. Thomas Malthus believed that the system would lead to early marriages and thus cause an explosion in population, while David Ricardo thought that the system would create a poverty trap where the poor would choose to work less, which would make food production fall, creating the space for a revolution.

Even if one were to make a case for NYAY, will it be possible to implement it in a country the size of India? In the recent past, Finland had launched a pilot programme based on the UBI, but this year the government has decided not to extend the programme. Similar pilot programmes have been launched in Oakland California, Iran, Canada, The Netherlands and Scotland. In the West, UBI is increasingly being proposed as a response to the unemployment that will be caused due to disruptive technologies such as AI and Robotics. The conspiracy theorists may not be wrong in saying that UBI might well be the panacea that the lobbyist from the large tech corporation are pushing for in countries such as India, Bangladesh, Vietnam etc., before they move in.

There is hardly any political party in any country that would oppose to help the masses caught in the vicious cycle of poverty, but it is essential to understand if the help that is being promised right before election is at all sincere. Let us try to understand the cost that will be associated with the promises made in the NYAY scheme and if at all the government can afford to spend without overshooting the fiscal deficit target. Out of the Rs 12,000 per month promised in the manifesto, even at an average cost of Rs 10,000 per month to be financed by the government, taking into account the balance Rs 2,000 as the own income of the beneficiary, it will cost the exchequer Rs 6 lakh crore to finance the proposed NYAY scheme for the targeted 5 crore families. To imagine that every poor will declare Rs 6,000 monthly income is misplaced. How will the government be able to verify the income of every family identified for the purpose? In Tamil Nadu, under the free TV programme of the DMK, TVs were delivered even to IAS officers and mansion owners, who took them and gave it to their house help, such as maids and drivers. At present, there is no data bank on the income of the rural poor with the Central or the State governments.

Even accepting the Congress figure of Rs 3.5 lakh crore per annum, then the fiscal deficit for the year 2019-20 will widen to 5.06%. If to this cost we add the cost of filling up 22 lakh vacant posts at an average monthly salary income of say Rs 30,000, and as the posts may carry different salaries this will cost another Rs 1 lakh crore including pension contribution, leave, medical benefits and other allowances. Then there is also additional cost of MGNREGA being extended to 150 days from the current 100 days, which will also have to be counted. Will the government discount the wages paid under MGNREGA for the income transfer? This has not been clarified. The cost of loan waiver for farmers across the country is anybody’s guess. By bringing fuel under GST of say 18%, there will be a huge loss, as in the current system, cess on fuel in different states is above 20%, which brings in major revenue to the state exchequer.

Congress has also promised special category status to Andhra Pradesh. What does it mean? It means that there will be no GST in AP. Industries from TN, Telangana and Karnataka will swarm into AP, creating a double whammy for the losing states, of employment and the SGST and for the Centre the CGST. Yet the 15th Finance Commission will compensate AP for the loss of SGST. The other states will then get less to that extent of the Central devolution. Can the Central fiscal deficit bear all this? Perhaps not and if carried out the fiscal deficit will revert to 6%, as it was during the heydays of the UPA, with inflation rising to 8% and above.

The social consequence of income transfer of idleness and non-availability of labour during crucial agricultural operations have also to be counted. The poor deserve a better deal, but the deal has to be calibrated to ensure that the country does not suffer. Will the Congress re-impose tax on capital gains, tax on inheritance and raise the marginal tax rate for the rich to 50% to reduce inequality and to finance these schemes? These are pertinent questions that ought to be answered as a part of the manifesto.

In a recent TV interview, Y.S. Jaganmohan Reddy, one of the leading Chief Ministerial hopefuls in the Andhra Pradesh Assembly elections, had stated that in his state alone there are nearly 1.7 crore BPL or White cards and even if 1.4 crore or 80% families are eligible for the NYAY scheme, nearly 4.2 crore, given an average of three members per family, will be benefited by it. As per the manifesto the NYAY scheme is targeted towards 5 crore families, who are “20%” in India. If AP alone has 1.4 crore families that qualify for the scheme, one can only imagine that the number of families across the entire country will far exceed the 5 crore families that the scheme proposes to support. Clearly, the numbers will have to reworked and according to YSR the targeted number of families should not be 20% of the BPL but 80% to make it an all-encompassing, fair and far reaching scheme.

Siddharth Sivaraman is Chief Business Officer, Andhra Pradesh, Aerospace Defence and Electronics Park.